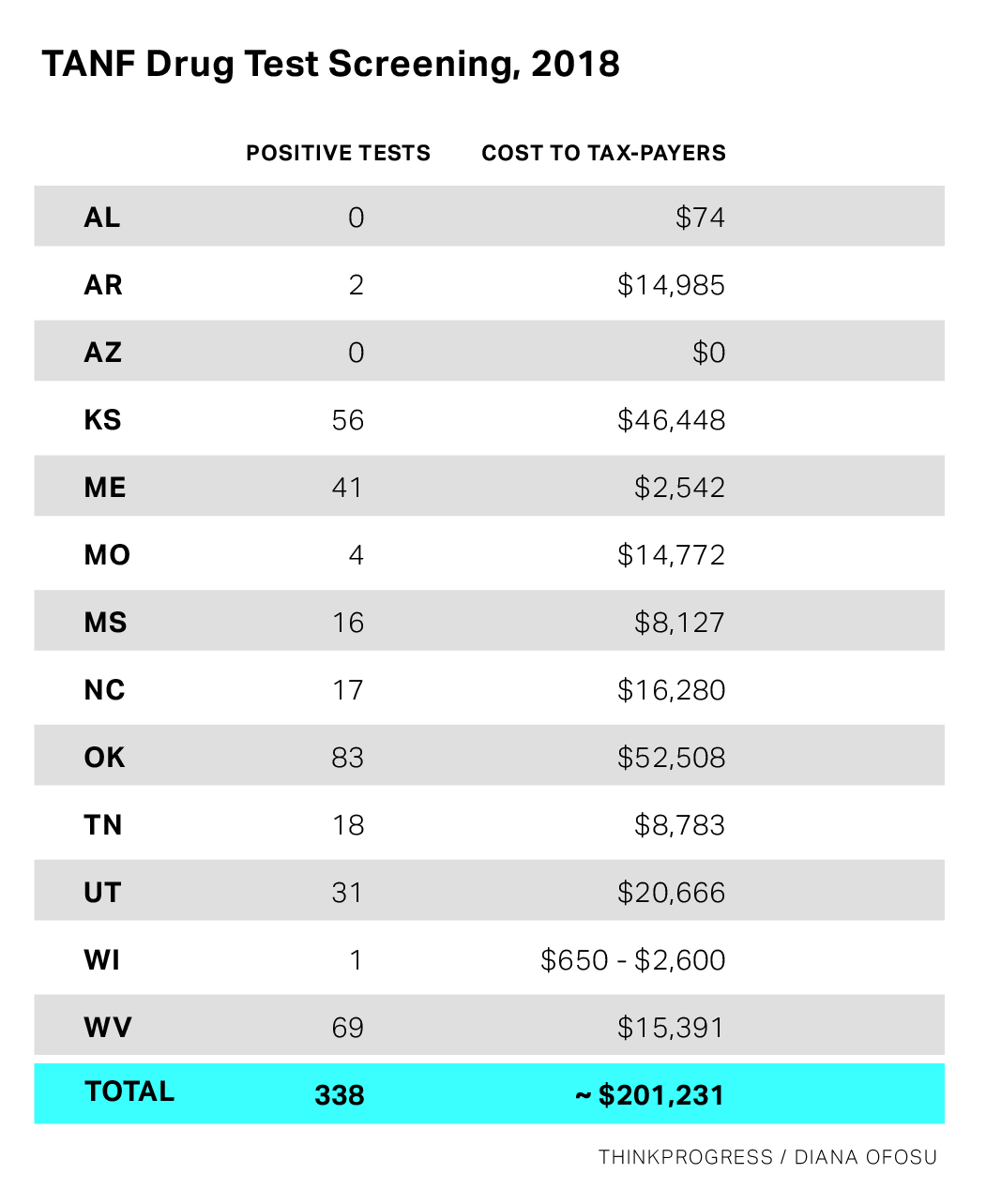

Thirteen states spent more than $200,000 screening federal-aid applicants for drugs last year. Only 338 people tested positive, according to data gathered by ThinkProgress.

In total, the states required more than 260,000 people to submit to drug screening or testing as a condition of receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which provides cash assistance to low-income people. In some states, not one person tested positive.

While universal drug testing for TANF was ruled unconstitutional in 2014, 13 states now require either applicants or beneficiaries with a “reasonable suspicion” of drug misuse be tested: Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, Kansas, Maine, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Utah, Wisconsin, and West Virginia.

If people refuse to cooperate, they cannot receive federal aid.

Such tests assume people who need federal assistance are more likely to misuse drugs than the general public — which advocates say amounts to shaming people who just need a little more help.

“It’s certainly not about helping people with substance misuse problems — it is about stigmatizing,” said Liz Schott, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research institute that works to reduce poverty.

Schott pointed to Tennessee, where lawmakers are trying to make the TANF requirement more punitive by requiring enrollees to submit to a hair follicle test instead of a urine test for more accuracy and by making it illegal to falsely answer the drug screening questionnaire.

Even though state data illustrates that even those who admit to illegal drug use on a screening questionnaire rarely test positive for drugs, no state has yet repealed its requirement.

“It is fundamentally unfair for some of us to obey the laws and get up and go to work every day, only to have a portion of the money that we work hard to earn go to pay for the housing, food, utilities, phones, gas and other benefits of others who sit at home all day unemployed and using drugs,” state Rep. Bruce Griffey (R), who is sponsoring the bill to add a hair follicle test and make it illegal to answer incorrectly, wrote in a March op-ed.

The rush of states adopting TANF drug testing requirements appears to have ground to a halt. Although new bills were introduced last year in seven states, none has enacted a new requirement since West Virginia in 2016, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Legislators in New Jersey and Texas have introduced drug testing bills in 2019, but officials in Maine and Wisconsin are trying to strike their requirements entirely.

Wisconsin currently drug tests recipients of TANF as well as those seeking food assistance. The federal government rejected a request in 2018 by former Gov. Scott Walker (R) to also test people who receive health care through Medicaid. Newly elected Gov. Tony Evers (D) is trying to repeal drug testing requirements for TANF and an assistance program called FoodShare in his proposed 2019-2021 budget proposal.

“Everyone deserves to be treated with dignity and compassion. Instead of trying to punish folks who have fallen on hard times by stigmatizing them or making them jump through hoops, Gov. Evers believes we should invest in health care and social safety-net policies that improve quality of care and strengthen families,” Evers’ spokeswoman, Melissa Baldauff, said in a statement to ThinkProgress.

Also bucking the trend is Maine. Gov. Janet Mills (D), who proposed repealing the TANF drug testing requirement in her latest budget. It’s likely she will succeed, as Maine’s legislature is now controlled by Democrats who’ve tried to reform TANF for some time but couldn’t under former Gov. Paul LePage (R). State lawmakers with oversight of the governor’s budget declined to comment.

Despite the slowdown, drug testing programs remain very much alive in the more than dozen states that mandate them.

ThinkProgress obtained data for each of those states:

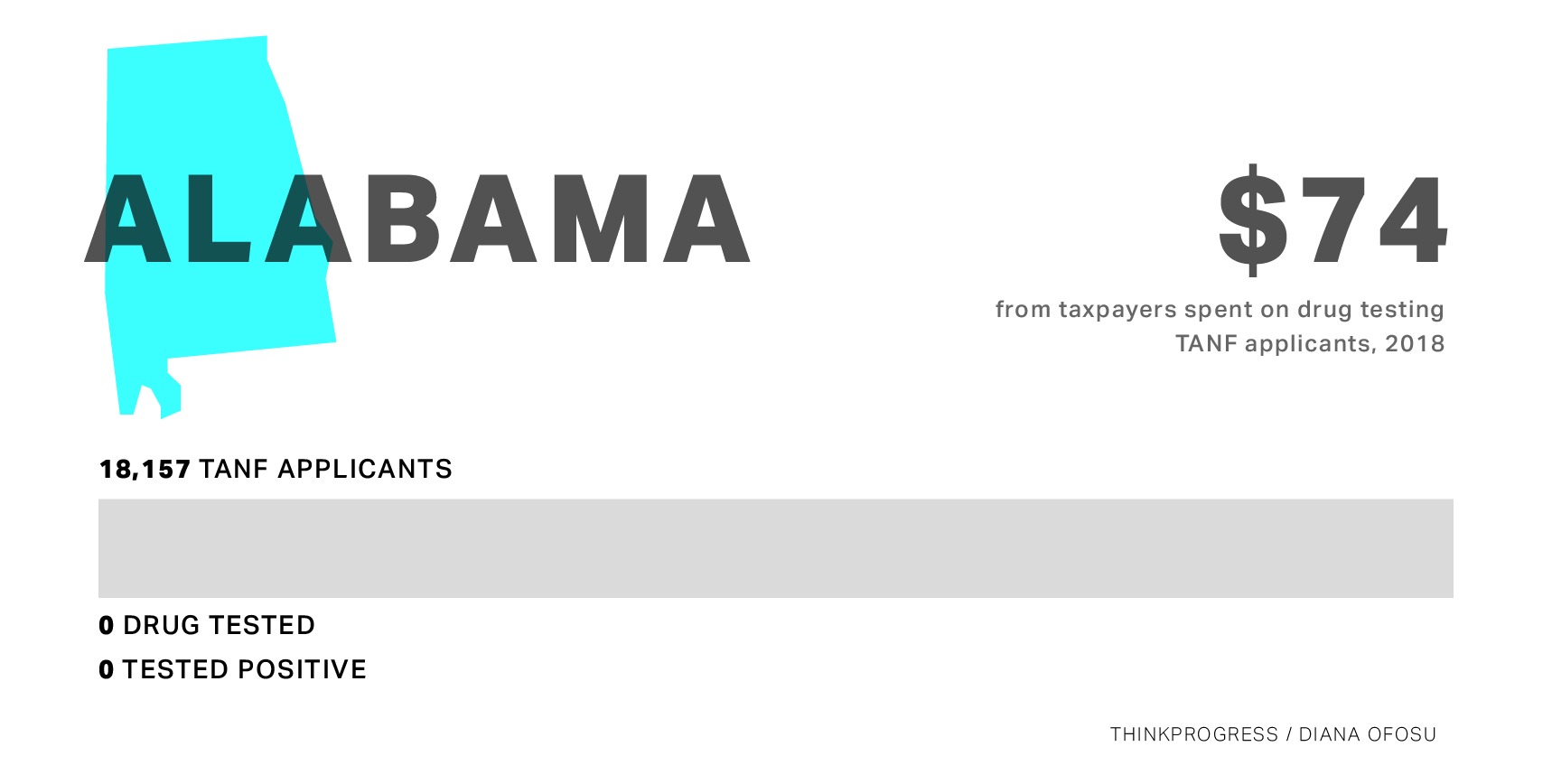

In 2018, 18,157 people applied for TANF benefits in Alabama, according to the state’s Department of Human Resources. Many of the applications were for children, who are not subject to screening.

The applicants were asked whether they had any prior drug convictions and whether they had recently used illegal drugs or misused prescription medications. As in 2017, not a single applicant was asked to take a drug test. The program cost the state $74.40 for supplies in 2018 — a small amount but one that served no apparent purpose.

Since the state legislature enacted the 2014 law requiring drug testing for TANF applicants and recipients with a “reasonable suspicion” of drug misuse, just three people have been tested and not a single person has tested positive.

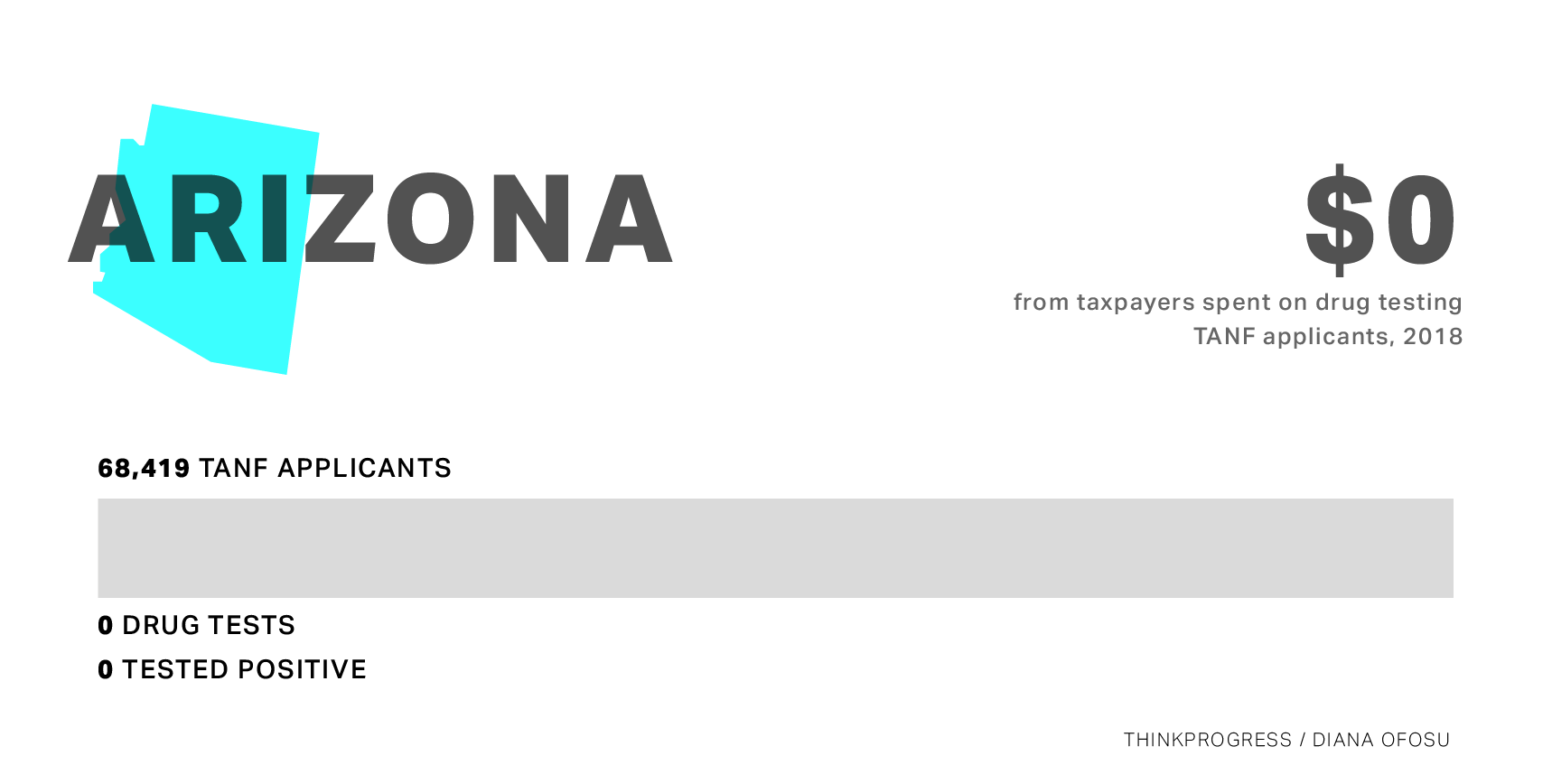

The Arizona Department of Economic Security considered 68,419 applications for TANF in 2018, but did not actually give a single applicant a drug test. Three were rejected for refusal or failure to show up for tests and the program did not cost anything for the year.

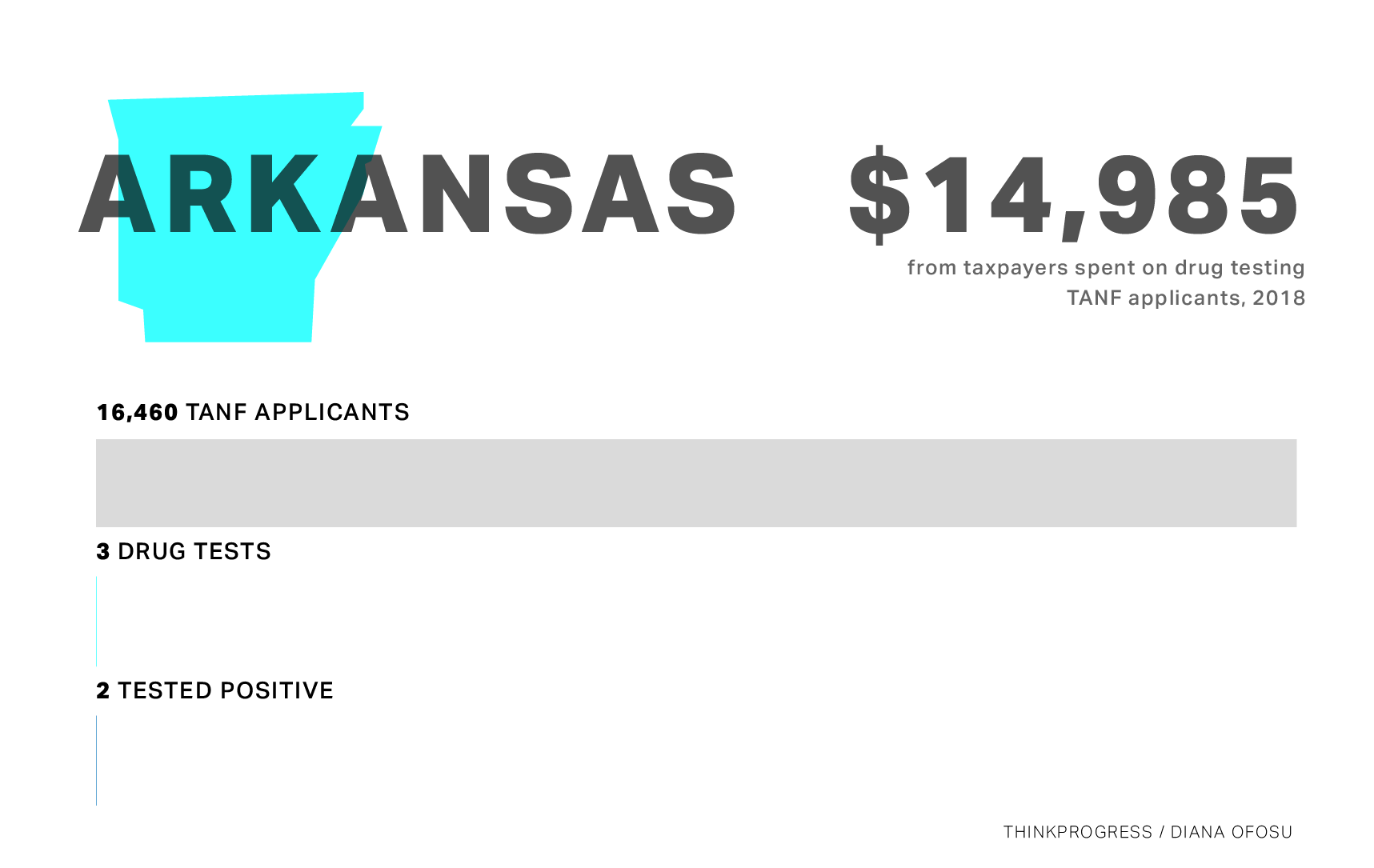

Of the 16,460 Arkansans who applied for TANF benefits in 2018, just six were referred for drug tests. According to the Department of Workforce Services, three people were rejected after refusing to take the test or failing to show up. Of the three applicants who were tested, two were positive.

The tests and staffing cost the state a total of $14,985 — about half the cost of the previous year.

The state legislature made the requirement permanent in January 2017, after the bill’s sponsor called the 2016 pilot a success and noted that the roughly $30,000 annual price tag was much lower than the $1.2 million cost some predicted. But in 2016, 2017, and 2018, the result has been the same: just two positive tests per year.

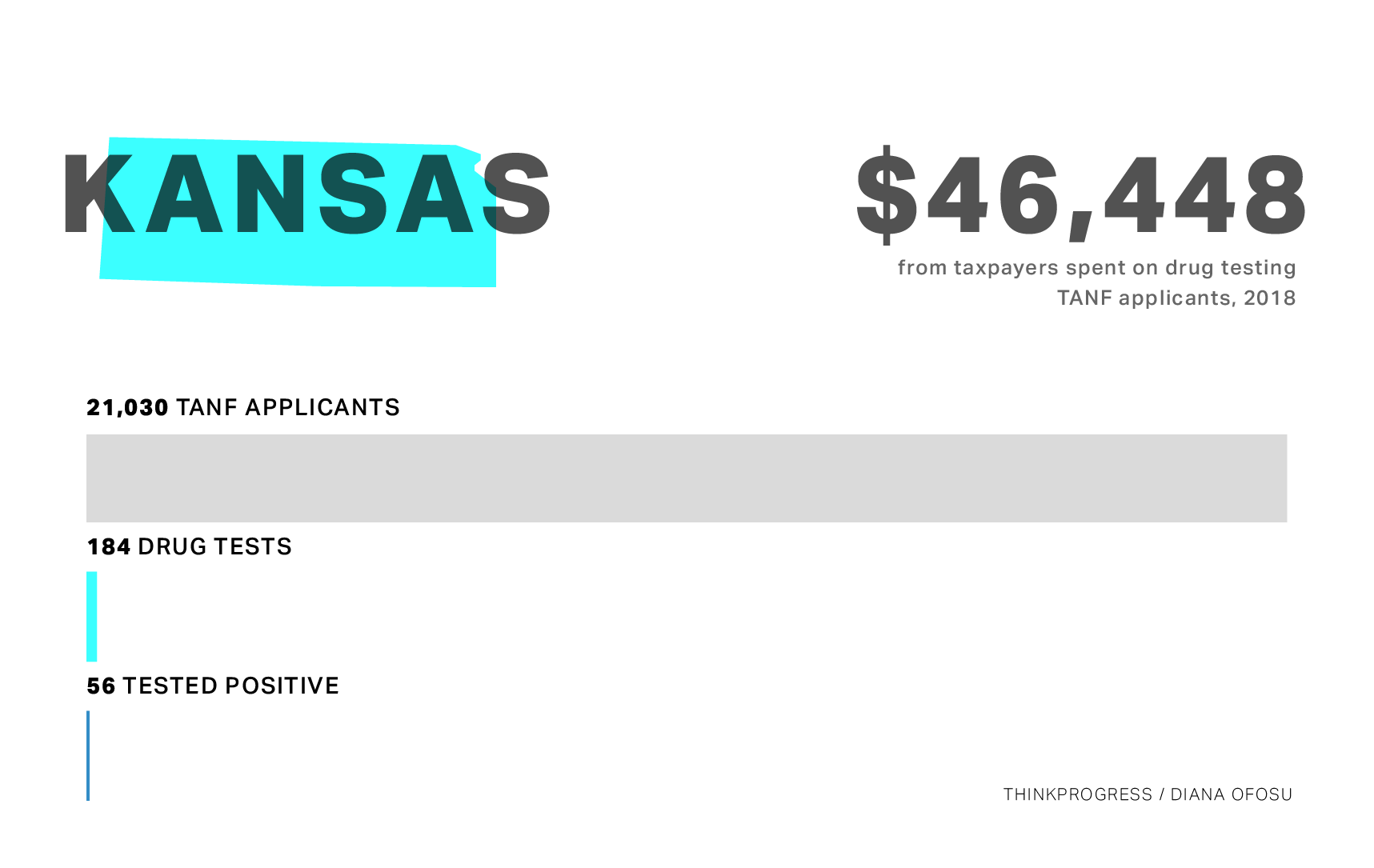

In 2018, 21,030 Kansans applied for TANF. The Department for Children and Families screened them and required 228 people to take drug tests based on “reasonable suspicion.” Of the 184 who complied, 56 tested positive.

The cost for the screenings was $46,447.94.

Of the 7,941 TANF applicants in Maine in 2018, 41 were asked to take drug tests. While all 41 tested positive, a spokesperson for the state’s Department of Health and Human Services told ThinkProgress that every one of those positive tests was for legal substances — either marijuana or methadone.

The state spent $2,542 for the tests and found no sign of illegal substances. This is a dramatic increase from 2017, when the state spent a third of that and drug tested only seven people.

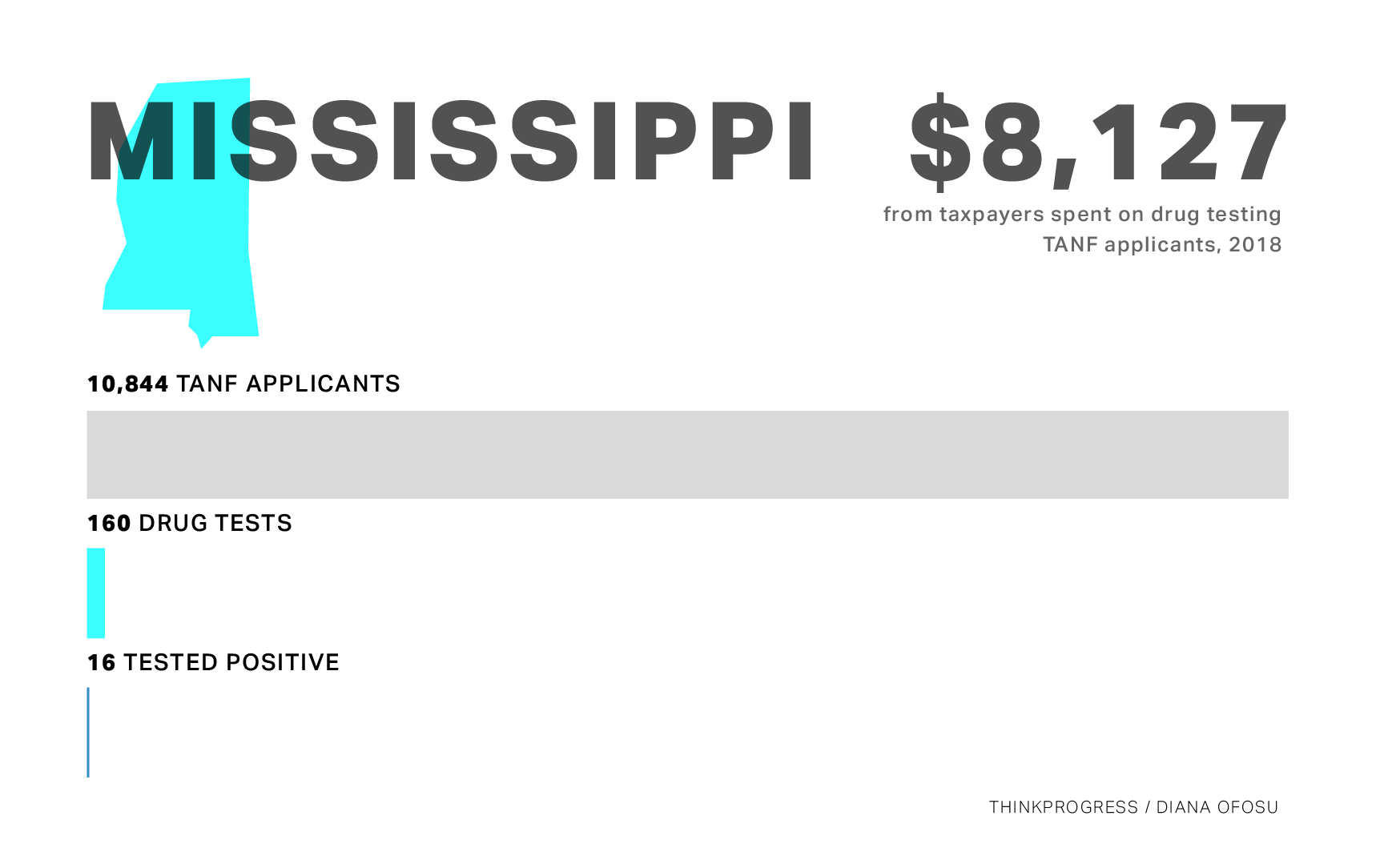

The Mississippi Department of Human Services spent $8,127 in 2018, screening 10,884 TANF applicants and requiring 161 of them to take a drug test.

Of those tested, just 10% — or 16 people — tested positive. One person refused or did not show up.

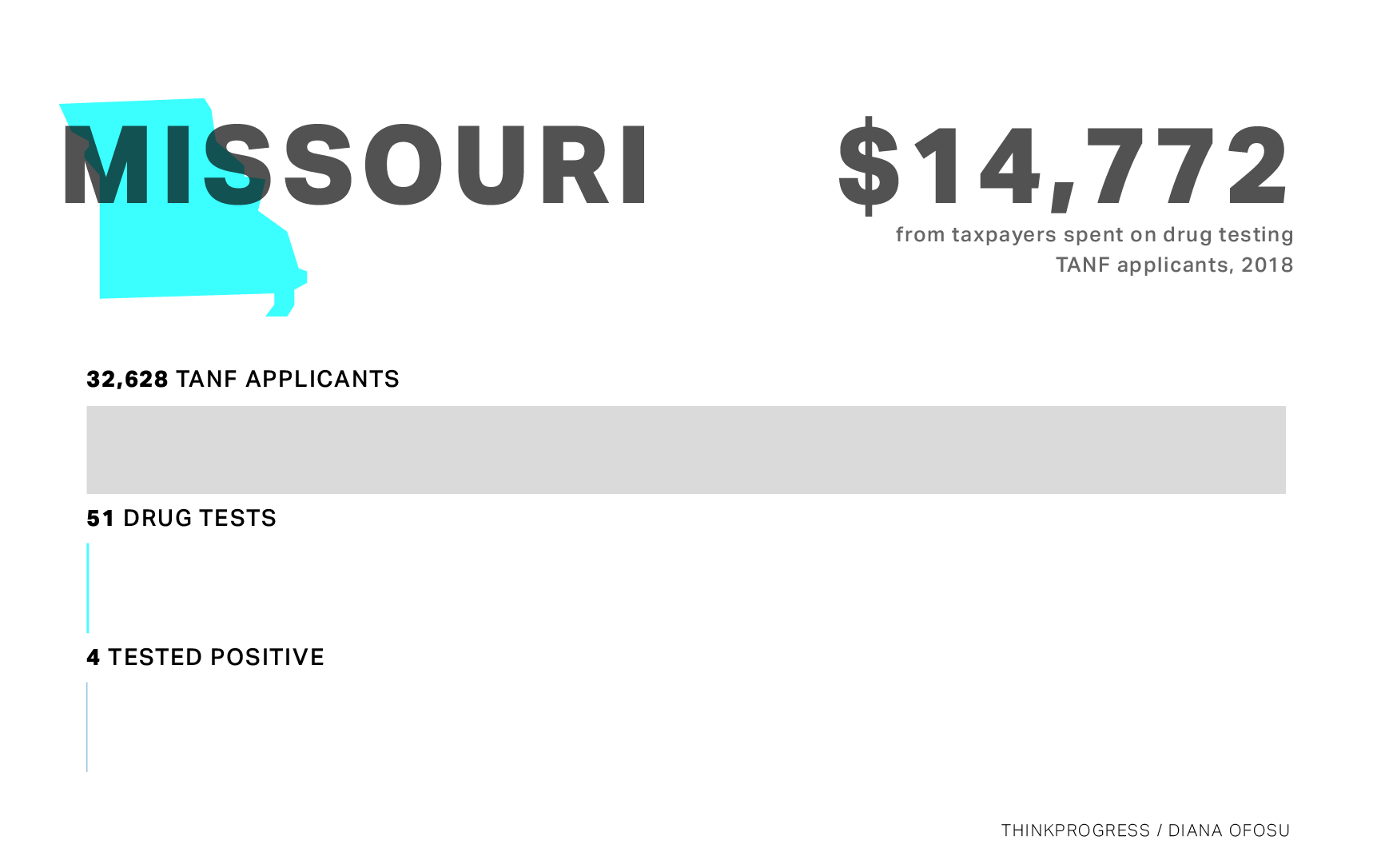

Last year, 32,628 Missourians applied for TANF. After screening, 243 of those were required to take a drug test, but just 51 actually did. Of those, only four tested positive — at a cost of $14,772.

In previous years, Missouri provided ThinkProgress with the appropriated amount, rather than the actual amount spent (ThinkProgress’ annual request has been for the “total cost”). With annual appropriations of more than $300,000 for the program, it appeared the state’s drug-screening process was vastly more expensive than those in other states.

In response to an inquiry about the high costs, a spokesperson for the Missouri Department of Social Services explained that “the actual expenditures” were significantly lower than the money appropriated, including information technology and drug testing costs. Although the state spent $420,193 to launch the program in fiscal year 2013, the annual operating costs have been below $72,000.

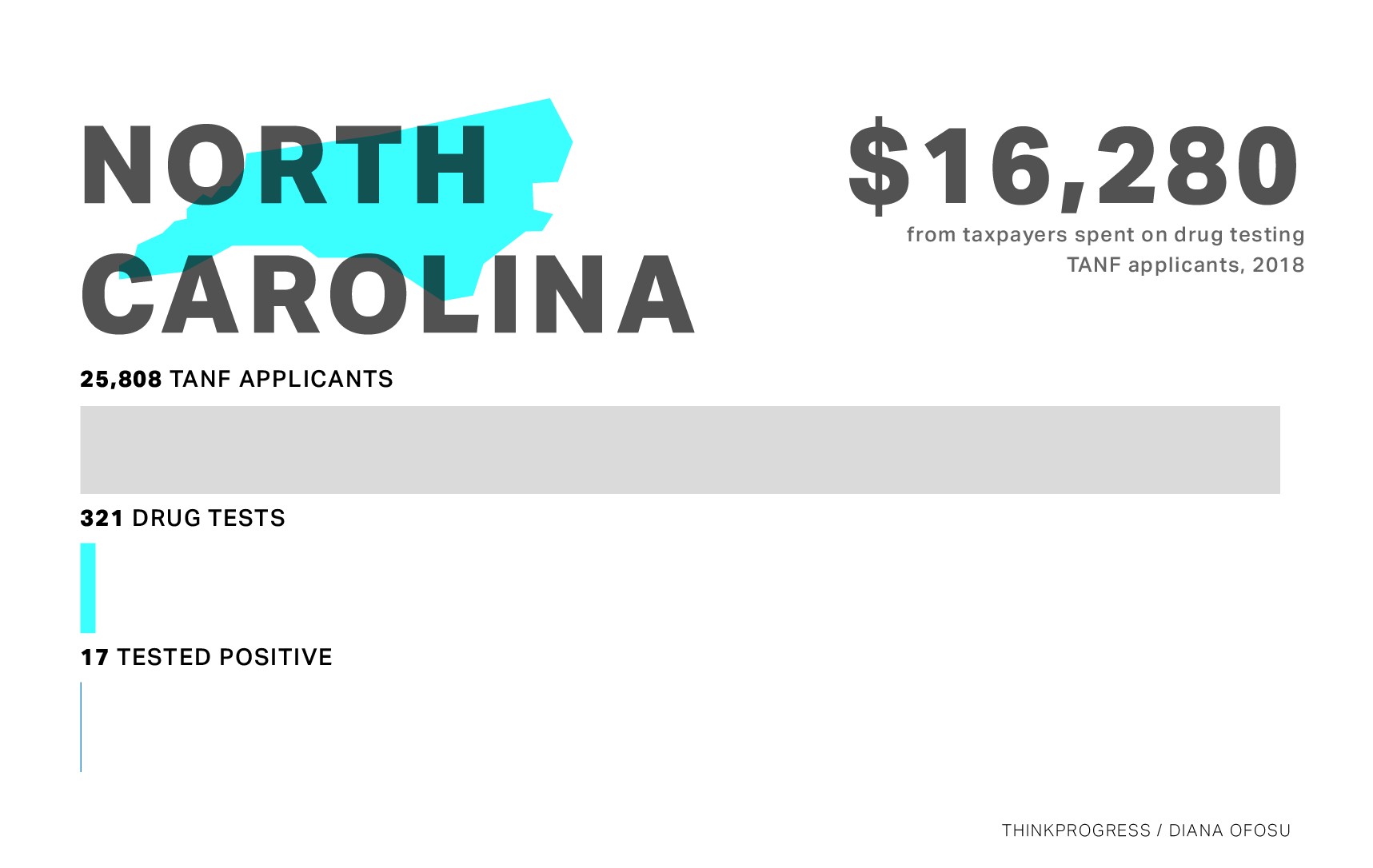

Last year, 25,808 people applied for TANF benefits in North Carolina. The state’s Department of Health and Human Services tested 321 for drugs, and 17 tested positive. Another 231 refused or did not show up for the test.

The testing process cost the state at least $16,280. A spokesperson for the department said the price per test dropped in July from $56.65 to $39.48, and that the totals did not include case workers’ time spent on the screenings.

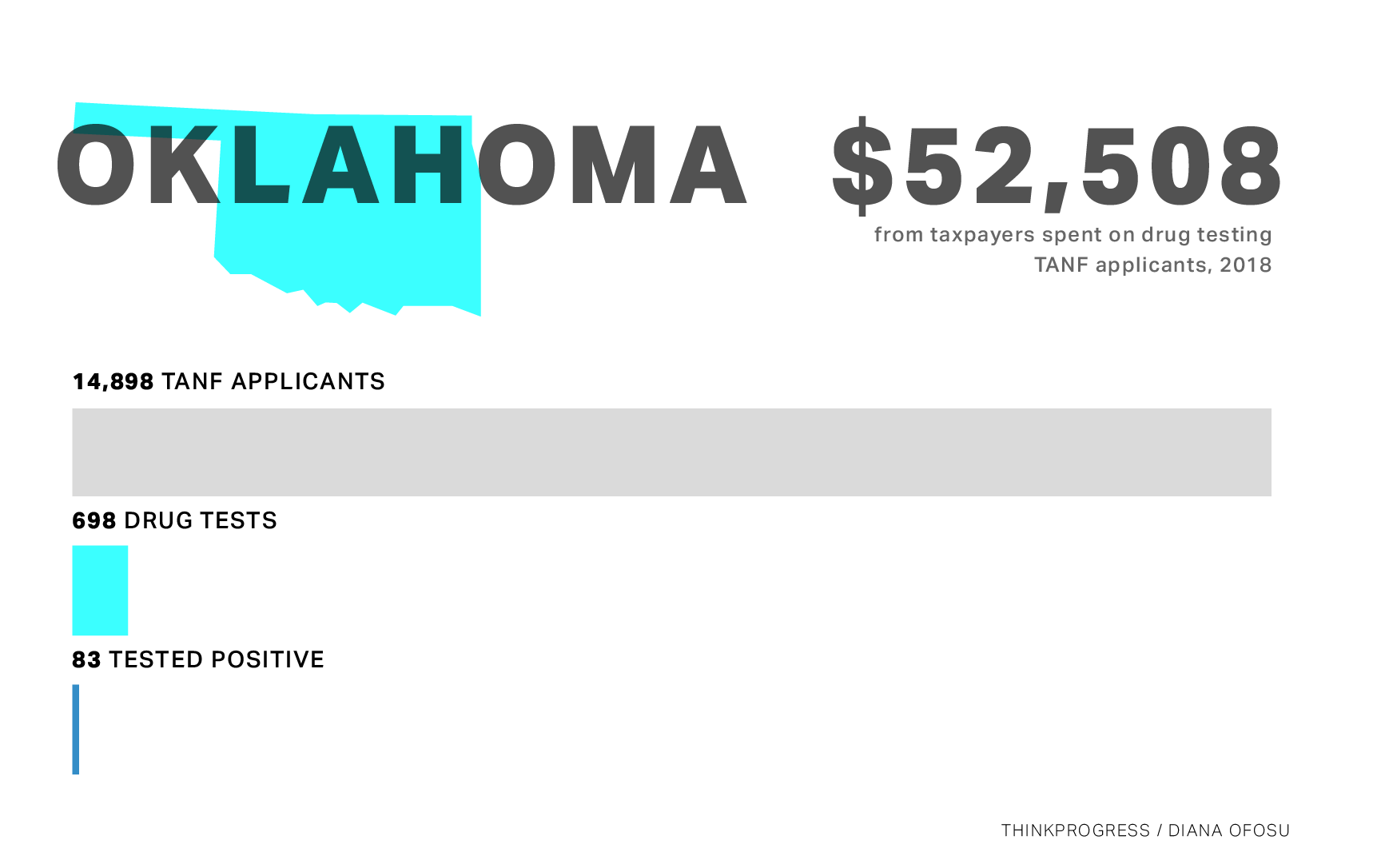

Of the 14,898 Oklahomans who applied for TANF benefits last year, 3,297 were screened and 964 of them were deemed suspicious to be using illegal drugs by the Department of Human Services. Of the 698 people who showed up for testing, 83 tested positive.

The process cost the state $52,507.99.

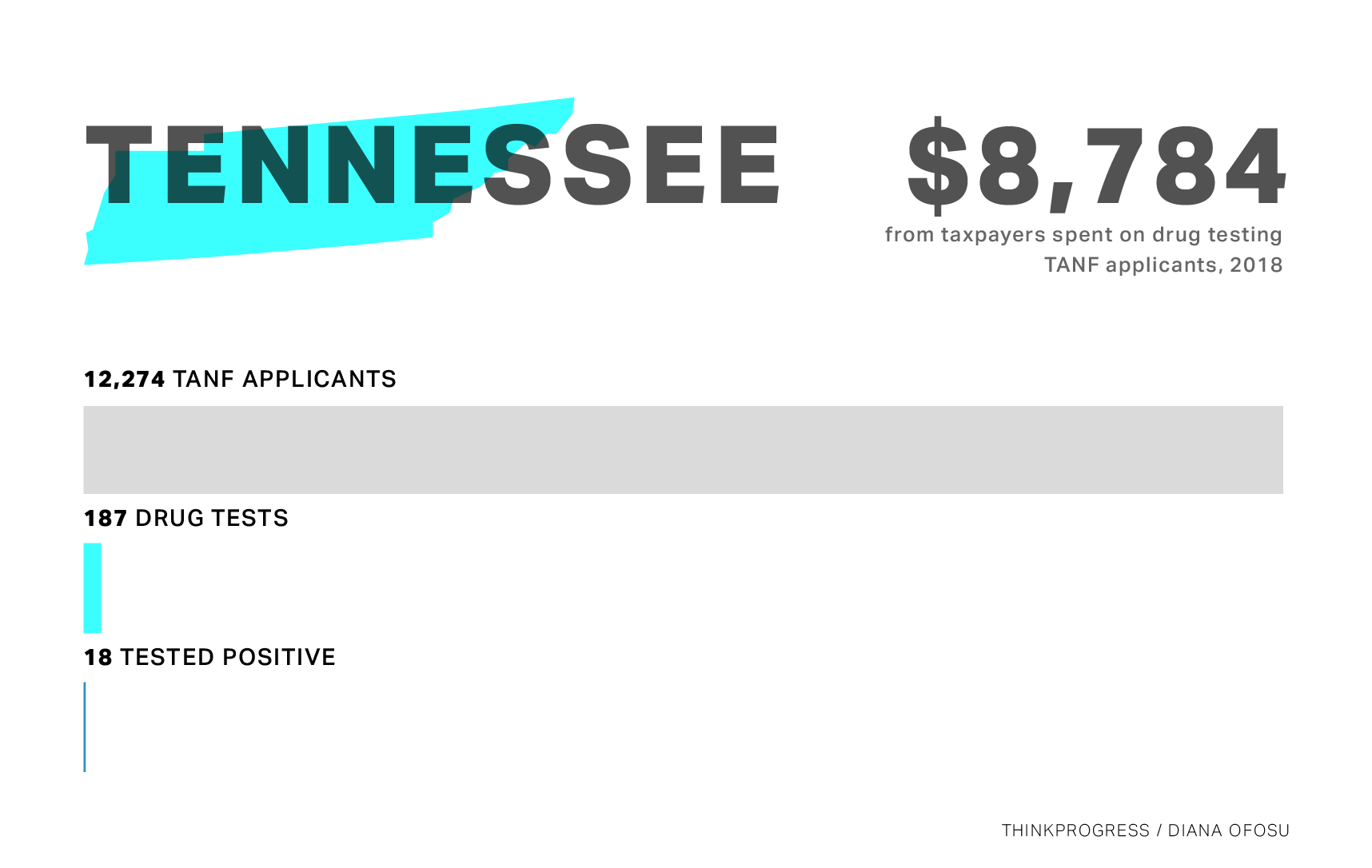

Tennessee’s Department of Human Services received 12,274 new applications for TANF in 2018. Of the 315 referred for drug testing, 187 completed the test and just 18 tested positive.

The cost of the program was $8,783.65.

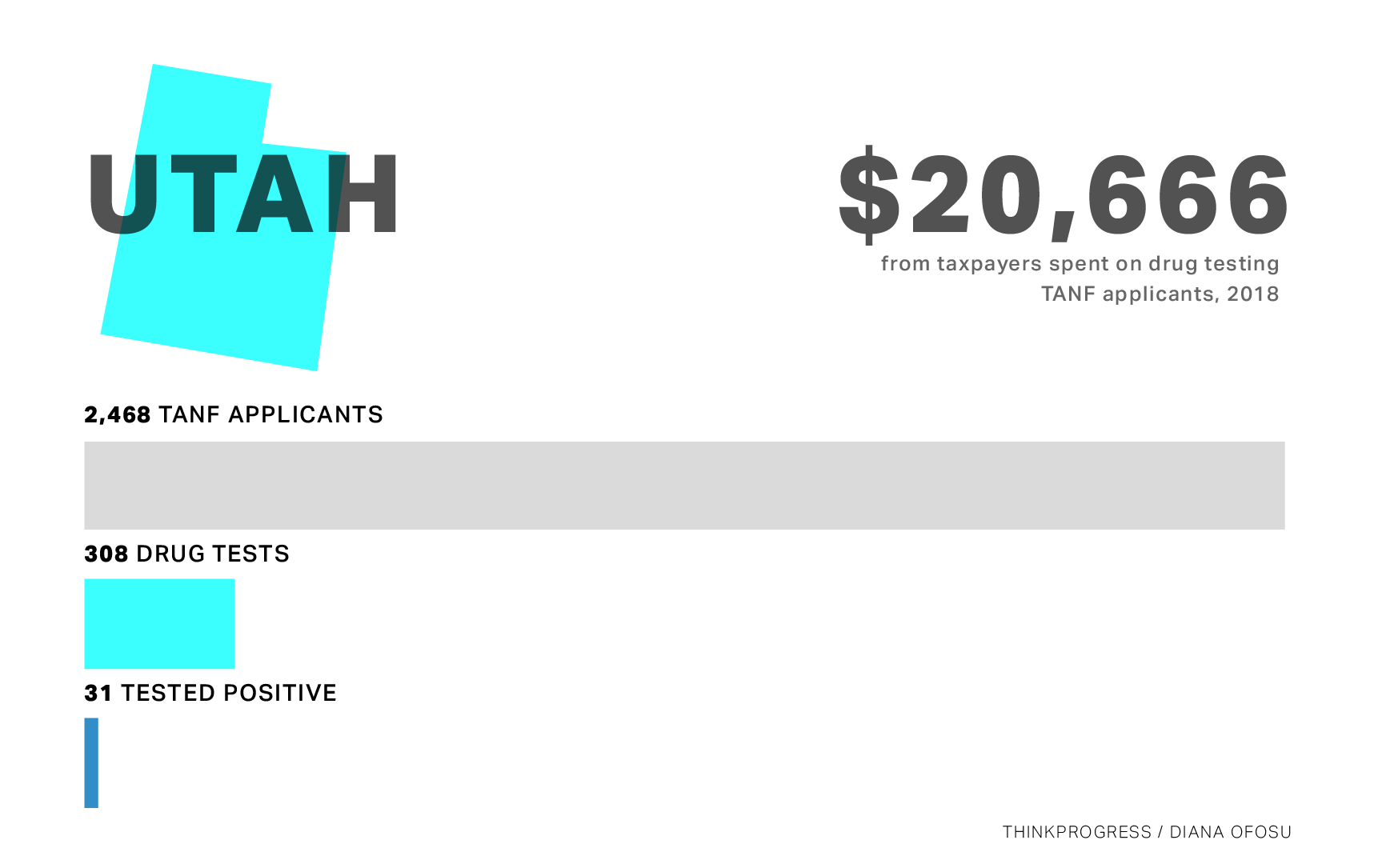

In Utah, 2,468 people received benefits through the Family Empowerment Program, the state’s TANF cash assistance program, in 2018. After screening, 404 were asked to take a drug test. Of the 308 who complied, 31 tested positive.

The cost of the tests was $20,666, though a spokesperson for the Department of Workforce Services said that did not include any staffing costs.

Of the 3,799 West Virginians who applied for TANF in 2018, 535 were deemed to have a reasonable suspicion of drug use. Of the 492 who took a drug test, 69 tested positive.

Not including in-house administrative costs, a spokesperson for the Department of Health & Human Resources said the cost was $15,394.68, a more than 50% increase from the previous year.

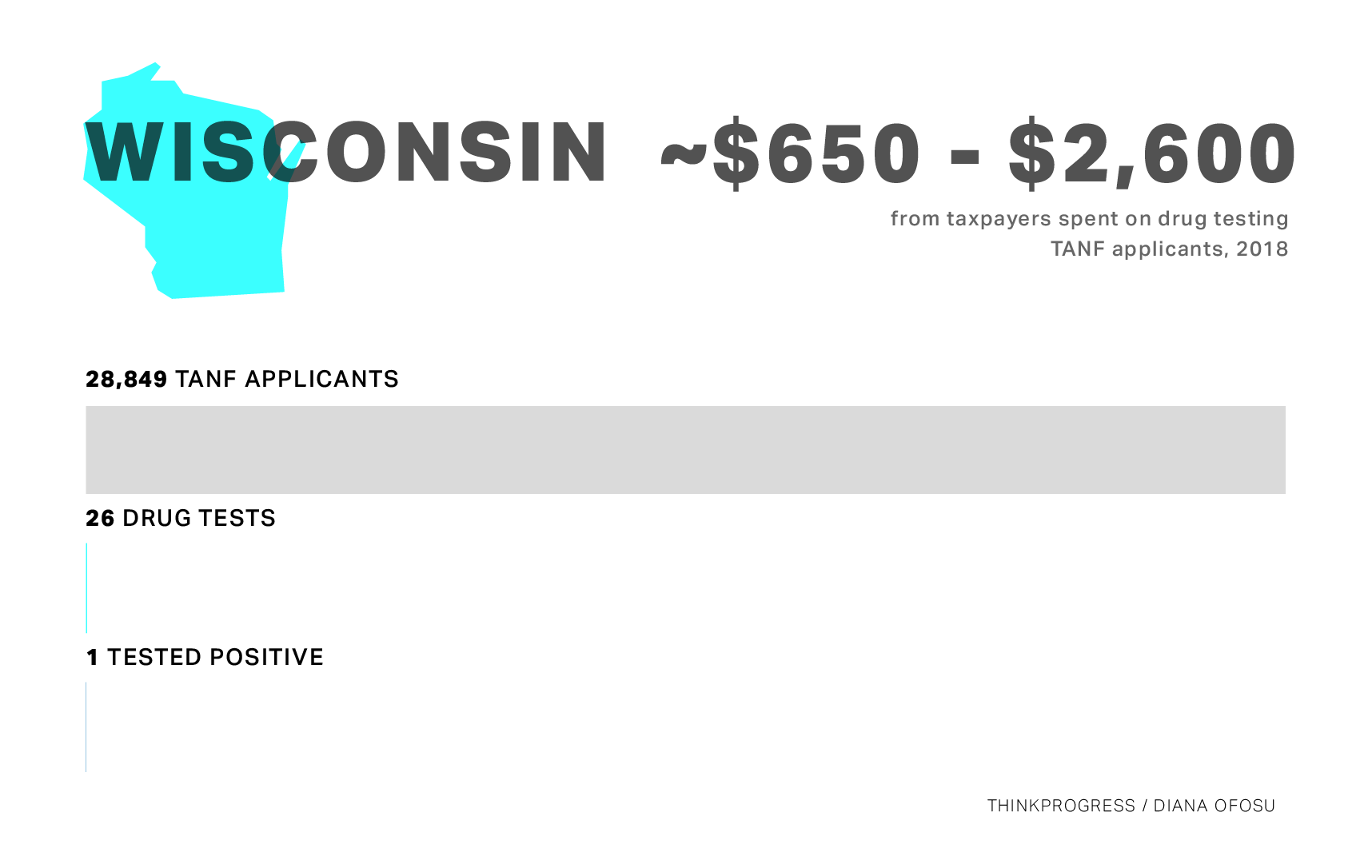

Though 28,849 people applied for TANF benefits in Wisconsin in 2018, only a small subset — 800 non-custodial parents — were subject to the state’s drug-screening process. From that group, 27 were asked to take a drug test, one refused, and one tested positive.

A spokesperson for the Department of Children and Families said the cost was somewhere between $650 and $2,600.