It’s been more than two months since a federal judge told the Trump administration to reunite all the families it separated as part of its failed “zero tolerance” immigration policy.

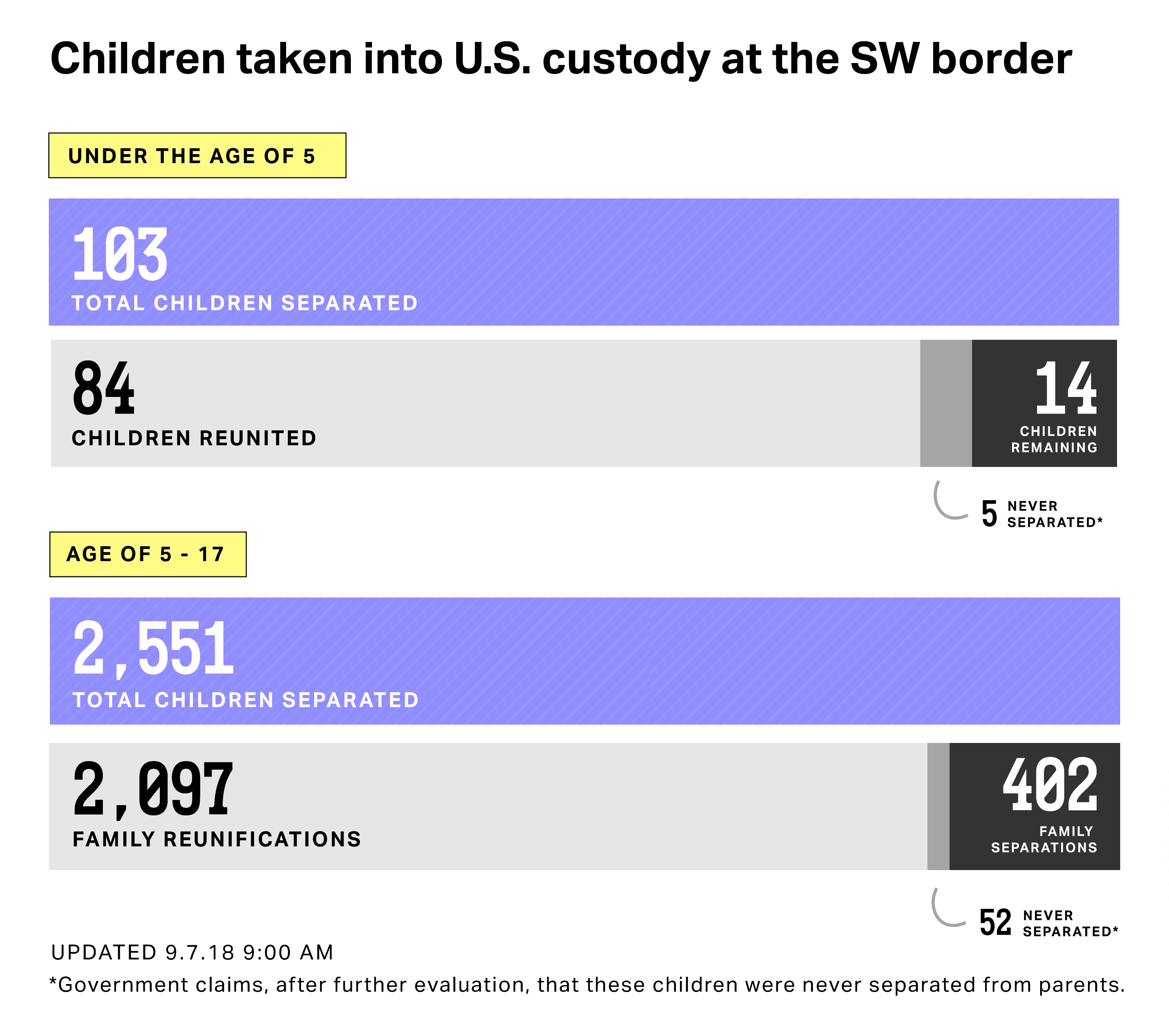

And yet, according to a new court filing on Thursday, 416 children are still separated from their caretakers. That number includes 14 kids under the age of 5.

This slow-moving process is indicative of the fact that the administration never had a plan to track and reunite families they’d torn apart by prosecuting parents entering the United States through official or illegal ports of entry (a misdemeanor crime). While officials have admitted the policy’s failure — saying “we need to be smarter if we want to implement something on this scale” — no one in the administration has been held accountable.

Meanwhile, California Judge Dana Sabraw, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and immigration advocates have been trying to help the administration reunite migrant families they’d separated in the spring. They’ve been meeting weekly with Trump officials to get the job done. The administration missed its court-mandated July 26 deadline to reunite all families — but Sabraw was sympathetic to the government as the majority of the more than 2,500 separated families were reunited in time.

According to the latest court filing, the 416 kids are still separated from their parents for a myriad of reasons. The Trump administration deported 304 parents to their country of origin and complicating matters more, the ACLU says they don’t have 17 parents’ phone numbers and 28 parents’ phone numbers are inoperative. And they need to speak to these parents to see if they want to be reunited in their country of origin or waive reunification rights so the children can pursue their asylum claims in the U.S.

The government also hasn’t reunited children with parents they report have criminal convictions or are unfit caretakers. Officials will give the ACLU a final evaluation of these cases on Friday, but already two cases in the court filing raise red flags:

Plaintiffs are particularly concerned about one family’s case involving a four-year-old child (who was three when he was first detained). The child’s mother was denied reunification based on an outstanding warrant from abroad, which alleges that she is a gang member. The mother denies this allegation, and at her immigration bond hearing, the immigration judge expressly found that this warrant was not sufficient evidence that the mother was a danger to the community. Defendants have nevertheless refused to reunify this family based on the parent’s alleged criminal history. This child is suffering greatly in detention and is at particular risk of grievous and irreparable harm.

Another case involves a 2-year-old child whose father has been denied several times. First, the government said it had to do with questions concerning parentage and now, it’s because of the father’s criminal history. The ACLU says they are only aware of the fact that the father pleaded guilty to a 2010 assault, “which has no bearing on his current dangerousness or ability to care for his child.”

The ACLU and other advocates want more information on why the government says 57 previously identified separated families are no longer considered to have been separated. This number has been fluctuating the past month, but the government insists now, after final evaluation, these kids are actually “unaccompanied” as their parents did not enter the country (il)legal and thus weren’t detained in immigration custody. There is no clarification on how five of those kids who are under 5 years old came to the United States unaccompanied.