This will be a story about Alex Kozinski, the disgraced former federal judge that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh clerked for. Yet it is also a story about Kavanaugh himself. It is a story about Kavanuagh’s repeated denials that he ever witnessed Kozinski “engaging in inappropriate behavior of a sexual nature.” It’s a story about why these denials are almost certainly lies.

If you want to understand just how nightmarish it was to clerk for Kozinski — especially for women — read Heidi Bond’s account of her own experience in Kozinski’s chambers. Kozinski summoned her into his office on at least three occasions, ostensibly so that she could fix a problem with his computer, only to show her pornographic images. In one of these cases, he asked her “does this kind of thing turn you on?”

Another time, Kozinski learned that Bond was reading romance novels during her dinner break. He ordered her to stop, telling her: “I control what you read, what you write, when you eat. You don’t sleep if I say so. You don’t shit unless I say so. Do you understand?”

Bond later wrote that Kozinski’s sense of humor was so vulgar and so frequently directed at his subordinates that “when I first arrived in chambers, the outgoing clerks suggested that we should watch The Aristocrats, a documentary about a notorious dirty joke, to prepare ourselves for the upcoming year.”

Several years ago I attended a legal conference where Kozinski was a featured speaker. Judge Kozinski was, up until the moment his name became synonymous with pervasive sexual harassment, a force of nature within the federal courts. He was brilliant and pugnacious. Conservative, but far more thoughtful and nuanced than the crop of unwavering ideological warriors nominated by Donald Trump.

And Kozinski was a “feeder judge,” one of the handful of the most prestigious federal judges whose clerks routinely were hired to clerk for Supreme Court justices. A clerkship with Alex Kozinski would make your career. It could rocket you into the highest echelon of the legal profession before your 30th birthday. Judge Kozinski knew this. Kozinski told Bond that he viewed her as a “slave.”

Bad bosses are hardly unheard of in a judiciary where the judges serve for life, clerks are sworn to secrecy about internal court matters, and top law students would give their left arm for the opportunity to clerk for the most prominent judges. But there was another aspect to Kozinski’s tyranny. Kozinski did not hide behind the confidentiality of his chambers to sexually harass his law clerks. He openly flouted it.

After Kozinski finished speaking at that aforementioned legal conference, a car pulled up outside the conference hotel and two attractive blonde-haired women exited the car. Judge Kozinski took the two women’s arms, and they escorted him into the car and away from the conference. I was later told that these two women were both his former law clerks.

Again, being a former Kozinski clerk meant you’d been initiated into the legal profession’s most elite tier. On this occasion, Judge Kozinski treated these two distinguished attorneys as if they were merely props.

There’s a surreal quality to the clerkship hiring market. Law schools publish student-run journals known as law reviews, and the top students all compete for the opportunity to work on these journals. The top law reviews all have powerful whisper networks that advise its members which judges are kind bosses, which ones are demanding, and which ones are Alex Kozinski. When I told a law school classmate I was interviewing with a judge known to be a tough boss, my classmate warned me “he’s a hell bird.” When a friend of mine who graduated at the top of her class applied for clerkships, the professor tasked with helping students secure these prestigious jobs warned her not to apply to Kozinski.

In 2008, Kozinski had to recuse himself from an obscenity case he was hearing after he accidentally published his porn stash online. This stash included “a photo of naked women on all fours painted to look like cows.”

When Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick clerked for one of Kozinski’s colleagues on the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, she called Kozinski’s chambers to speak to a friend who was clerking for him. Kozinski answered the phone, and soon asked Lithwick “what are you wearing?” In the years that followed, as Lithwick became one of the most prominent legal reporters in the country, Kozinski introduced himself to Lithwick’s husband as her “paramour.” The judge would great her with “another too-long, too-exuberant public kiss” when the two attended the same events.

Like Lithwick, I am also a member of the press. I knew about Kozinski. I knew because everyone knew. I knew because he made no effort to hide his antics. As Lithwick wrote last December, after news of Kozinski’s harassment was revealed to those of us who did not work on a law review:

This story really shouldn’t be about me. I never worked for Kozinski, and even though his behavior affected me, my future never depended on him. But here is the part that does implicate me: When a prominent journalist with a national platform chooses—year after year—not to report on an open secret, or agrees to slouch through yet another dinner or panel or cocktail party, how can it only be about the victims and the harassers? Because really, if you can’t tell a man to back off when you’re 50 and at the peak of your journalistic power, who is ever going to do it?

I knew about Kozinski. I could have reported out his behavior and I did not. It is one of my greatest failings as a journalist.

But I tell this story not to self-flagellate. I tell it to convey just how widespread news of Kozinski’s behavior was among a certain kind of law school graduate. If I, a liberal who applied only to liberal judges’ chambers and didn’t have the stratospheric grades needed to secure a Kozinski clerkship even if I wanted it, knew so much about Kozinski’s behavior, imagine what Judge Kavanaugh must have known.

Imagine what Judge Kavanaugh must have heard while he was Kozinski’s law clerk.

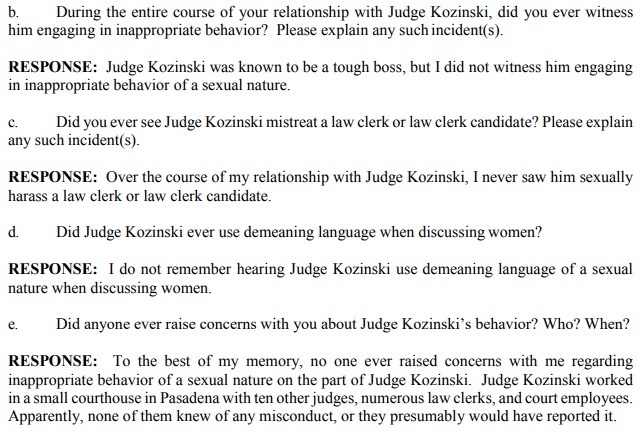

Which brings me back to Kavanaugh’s response to questions about what he saw and what he heard from Alex Kozinski. Consider the Supreme Court nominee’s response to a series of written questions from Sen. Chris Coons (D-DE).

There’s a lot to unpack here. For one thing, when asked if Kozinski ever used “demeaning language when discussing women,” he responds that he does not recall Kozinski using “demeaning language of a sexual nature.” That’s not a complete answer to Coons’ question.

For another thing, Kavanuagh’s statement that, if some other court employee had known about Kozinski’s behavior, “they presumably would have reported it” suggests that the man-who-would-be-a-Supreme-Court-justice has no clue how power dynamics work in the workplace. Kozinski had the power to launch his clerks into the legal stratosphere, but he also had the power to destroy them — a single call from a federal judge to a law firm warning them not to employ a former clerk would end that clerk’s career. And even Kozinski’s fellow judges often needed his vote when they heard cases together.

It’s hard to fault a judge who decided not to blow the whistle on Kozinski because they didn’t want Kozinski, motivated purely by spite, to vote against them in a critical case.

Kavanaugh’s repeated claims that he has no recollection of Kozinski making sexually inappropriate comments to a law clerk — or that he never even heard anyone raise concerns about such behavior by Kozinski — are quite literally unbelievable. Unless Kozinski became a completely different person between the early 1990s, when Kavanaugh worked for Kozinski, and the mid 2000s, when Bond did, it is difficult to imagine Kavanaugh working in the kind of environment Bond describes and never hearing an inappropriate remark.

And even if Kavanuagh somehow did not see his boss’ behavior while he was Kozinski’s clerk, it is equally unbelievable that Kavanaugh could have traveled in these elite circles of the legal profession and somehow avoid hearing it discussed. Again, Kozinski’s behavior was so brazen that he would inappropriately kiss prominent members of the media in public settings.

All of which is a long way of saying that, when Judge Kavanaugh says that he has “never done anything like” holding a woman down and trying to rape her — as psychology professor Christine Blasey Ford says that Kavanaugh did to her in high school — it’s a good idea to take Kavanaugh’s own statement with a grain of salt.