Pretty much everyone with a stake in America’s health care system hates Trumpcare.

The biggest doctors’ group in the country, the American Medical Association (AMA) came out against House Republicans’ health care bill on Wednesday, warning that it “would result in millions of Americans losing coverage and benefits.” The organization is joined in its opposition by the American Hospital Association and the AARP.

America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), the leading industry group representing health insurers, stopped shy of denouncing the entire bill, but still objected to provisions that could destabilize insurance markets, cut financial assistance to help people afford coverage, and “weaken Medicaid coverage of mental health and opioid addiction.”

All of these groups are taking a position stemming from self-interest. Doctors stand to lose patents if millions of Americans lose coverage or wind up on inferior plans. Many hospitals restructured their business models to account for the Affordable Care Act, and would need to make more costly changes if the law were significantly altered. AARP is a membership organization representing older Americans, who are likely to face the greatest financial burdens if the House bill becomes law. AHIP obviously doesn’t want to see its own markets destabilized.

But these interest groups also may be millions of Americans’ best hope of keeping their health insurance.

Republican lawmakers do not appear particularly concerned that their proposal could strip Americans of their health care. Indeed, most of the criticism of the House Republican bill within the GOP caucus comes from hardline conservatives who are upset that it does not cut even deeper.

But if these lawmakers won’t listen to the millions who could lose coverage, maybe they will listen to a different constituency that has traditionally appealed to Republican lawmakers — well-moneyed interest groups concerned with their bottom line.

The art of the deal

The history of health care legislation in the United States has, to a large extent, been the history of Congress learning to manage interest groups with a financial stake in the issue.

For nearly a century before Obamacare, center-left leaders in the United States dreamed of enacting a universal health insurance plan. Yet, as the Roosevelt Institute’s Richard Kirsch chronicles in a 2013 law review article, they were thwarted at nearly every turn by interest groups such as the AMA.

The AMA likened President Franklin Roosevelt’s plans to include health coverage in his Social Security proposals to “revolution” and “socialism and communism.” After President Harry Truman promised “national, compulsory health insurance,” the AMA launched a national campaign to shut down Truman’s plans. Physicians hung 65,000 posters in their offices showing a country doctor over the caption “Keep Politics Out of This Picture.” Health providers and their allies distributed 55 million pamphlets featuring a fabricated quote that was falsely attributed to Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin — “Socialized medicine is the keystone to the arch of the Socialist State.”

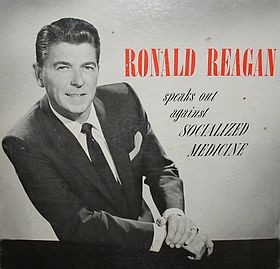

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the AMA recruited Ronald Reagan, then just an actor, as the centerpiece of a campaign known as Operation Coffee Cup. Doctors’ wives would invite their friends over for coffee, where they would listen to a recording of Reagan warning that Medicare is “a short step to all the rest of socialism” and urging them to write their members of Congress and tell them to oppose universal health insurance for the elderly.

“If you don’t do this and if I don’t do it,” Reagan told the many gatherings where his recording was played, “one of these days you and I are going to spend our sunset years telling our children and our children’s children, what it once was like in America when men were free.”

In the Clinton years, the AMA backed off this level of strident opposition. Yet the mantle of opposing health reform was carried by a coalition of health insurers. That coalition is best remembered for its “Harry and Louise” ads claiming that “the government may force us to pick from a few health care plans designed by government bureaucrats.”

By 2009, when President Obama came into office, reformers believed that their best chance to succeed where Roosevelt, Truman, and Clinton had failed was to win the support — or, at least, mitigate the opposition — of key industry players who could finance opposition to the bill. The alternative, they feared, was likely to be no law — and thus thousands more Americans condemned to die every year because they lacked health coverage.

Accordingly, the Affordable Care Act was a series of trade-offs, coupling reforms intended to benefit millions of Americans with other provisions that mitigated the cost of those reforms for insurers and health providers.

One of the law’s core structures, for example, is its “three-legged stool” of protections for people with preexisting health conditions, financial incentives to bring people into the health insurance market, and tax credits to help them afford coverage.

This structure enables millions of Americans to obtain insurance, but it also addresses one of the insurance industries most legitimate concerns about health reform. Though the law’s individual mandate, which requires people to either carry health insurance or pay somewhat higher income taxes, was unpopular, it was also necessary to preserve insurance markets if insurers were no longer able to exclude people with expensive medical conditions.

If people are allowed to wait until they become sick to purchase insurance, they will drain all of the money out of an insurance pool that they haven’t paid into, driving up costs for everyone else and potentially threatening the market itself. By causing people to buy insurance while they are still healthy, the individual mandate prevents this collapse and allows insurers to continue operating.

Other provisions of the law balance cuts to one source of revenue for health providers with new sources of revenue to compensate for those losses.

For example, Obamacare cuts the amount Medicare pays to health providers by hundreds of billions of dollars. This offsets much of the cost of the law’s provisions expanding health care to the uninsured, while also extending Medicare’s solvency. At the same time, however, these cuts hit hospitals and other health providers that are now paid less for their services.

For this reason, the Affordable Care Act was designed so that the influx of newly insured patients would offset the financial hit to providers caused by the lower Medicare payments. It was a delicate balancing act, but one that ultimately helped bring the AMA and the AHA on board.

No solution

These deals are why many Americans hate politics. But they are often an essential part of good policy making. Hospitals, health providers, and the insurance industry are all self-interested actors eager to make a buck, but that doesn’t mean that their concerns are wrongheaded or can safely be ignored.

The insurance industry’s concern about protecting people with preexisting conditions without also taking steps to bring healthy people into the market is a valid one, for example, and it is rooted in a very unfortunate history.

Insurance executives may be driven only by profits, but they also had a point.

As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg explained in her opinion in the first lawsuit seeking to kill Obamacare, several states — including New York, New Jersey, Washington, Kentucky, Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont — enacted protections for people with preexisting conditions in the 1990s that were similar to the ones included in Obamacare. But those states didn’t also require all of their residents to purchase health insurance.

“The results were disastrous,” Ginsburg wrote. “ ‘All seven states suffered from skyrocketing insurance premium costs, reductions in individuals with coverage, and reductions in insurance products and providers.’”

Insurance executives may be driven only by profits, but they also had a point. And they needed to be at the table to make this point to lawmakers, lest Obamacare wind up causing more problems than it solved.

This dilemma won’t go away now that the Obama family no longer lives in the White House. The open question is whether a new Congress will listen to interest groups that, for all that they have a financial stake in the health care wars, also know a tremendous amount about health policy.

There are good reason to worry that congressional Republicans cannot be moved, even by industry groups that could punish lawmakers in 2018 if those lawmakers do not heed the groups’ advice.

Think back to 2013. Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX), backed by conservative groups like Heritage Action, wanted to shut down the government until the Affordable Care Act was defunded. Republican leaders were far from enthusiastic about this plan, but they were too afraid of their right flank to stop Cruz. And the shutdown did happen — even though groups like the United States Chamber of Commerce, a powerful conservative lobby and the leading advocacy group for big business, tried to stop it.

In a letter that was cosigned by 250 other business organizations, the Chamber warned that “it is not in the best interest of the employers, employees or the American people, to risk a government shutdown that will be economically disruptive and create even more uncertainties for the U.S. economy.” According to the Chamber and its allies, Congress should “act promptly to pass a Continuing Resolution to fund the government and to raise the debt ceiling.” Congress paid little mind.

In 2013, Republican leaders could allow the shutdown to happen, wait for their poll numbers to drop, and then allow conservative enthusiasm for the shutdown to burn away naturally. The government shut down for only 17 days, and it reopened with plenty of time for Republican lawmakers to rehabilitate their image before the next election.

Today, the stakes are much higher. A health policy disaster is much harder to survive than a government shutdown. If the House Republican bill becomes law, millions are likely to lose care. Without insurance, some people could die. Others could be irreversibly plunged into financial ruin.

Meanwhile, insurance markets could collapse. Hospitals could be forced to lay off doctors and nurses.

The mightiest and most knowledgeable players within the health industry are warning of these consequences. The question is whether Republican lawmakers can look past their ideology for just long enough to listen to what they are being told.