Donald Trump is so very right about this.

Mitch, use the Nuclear Option and get it done! Our Country is counting on you!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 21, 2018

Trump says that he would be “proud” to shut down the government unless Congress gives him over $5 billion to fund a border wall. But there aren’t 60 votes in the Senate to pass such funding. Trump thinks that the funding may pass if Senate Republicans eliminate the filibuster, reducing the amount of votes needed to enact legislation to 51.

The “nuclear option,” refers to a process that allows the Senate to change its own rules by a simply majority vote. Democrats used this process in 2013 to eliminate the 60-vote requirement to confirm non-Supreme Court nominees. Republicans used it in 2017 to eliminate the same requirement for Supreme Court nominees. They could use it again on Friday to allow any legislation to pass the Senate with 51 votes, potentially giving Trump the Mexican border wall he so craves.

If Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) were to nuke the Senate, the short term impact would be unfortunate. Trump’s wall is the racist, wasteful fantasy of a racist, wasteful president. A future president would need to build a big, beautiful wrecking ball, and make rich people like Donald Trump pay for it with their taxes.

But there’s also rarely been a safer time to eliminate the filibuster. Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) becomes House speaker in less than two weeks. Republicans have a very slim majority in the Senate and are unlikely to ram much legislation through during the holidays. If McConnell were to nuke the filibuster, Trump would get his wall funding, but Democrats would quickly gain the ability to block any additional lawmaking.

And in the long term, a filibuster-free Senate would be a huge boon for liberals. There’s a very easy explanation for why McConnell did not nuke the legislative filibuster, even as his caucus repeatedly embarrassed itself by failing to pass high profile legislation. If the filibuster falls, American government will grow, Democrats will become stronger, and Republicans will grow weaker.

Veto points

The reason why the filibuster favors Republicans is fairly basic. Nations with less complicated legislative processes are more likely to, well, enact legislation. Over time, that will lead to larger, more robust government.

In The Economic Effects of Constitutions, European economists Torsten Persson and Guido Tabellini determined that higher government spending and larger welfare states correlate with certain forms of government, while nations more similar to the United States tend to be more parsimonious.

Among other things, Persson and Tabellini compared presidential democracies like the United States, where the chief executive is elected separately from the legislature, to parliamentary democracies, where the chief executive is chosen by the legislature. Their findings are stark. “Presidentialism reduces the overall size of government . . . by about 5% of GDP.”

When presidential democracies do spend money, moreover, they tend to do so less equitably. As the two economists explain in a summary of their work, “in parliamentary democracies, a stable majority of legislators pursue the joint interests of its voters. Spending thus optimally becomes directed toward a broad majority of voters.”

By contrast, “in presidential democracies, the (relative) lack of such a majority instead pits the interests of different minorities against each other.” The result is that “programs with broad benefits suffer, and the allocation of spending favors minorities in the constituencies of powerful officeholders, for example, the heads of congressional committees in the United States.”

There are a myriad of reasons why presidential systems tend to produce stingier, less equitable government. One of them is that presidential governments tend to have more veto points — that is, there are simply more opportunities to block legislation in most presidential systems than in parliamentary governments.

As professors Evelyne Huber, Charles Ragin, and John D. Stephens wrote in the American Journal of Sociology, “those features of constitutions that make it difficult to reach and implement decisions on the basis of narrow majorities — and that, conversely, let minority interests obstruct legislation — will impede far-reaching reforms in social policy.”

“Aspects of constitutional structure that disperse political power and offer multiple points of influence on the making an implementation of policy,” they suggest, “are inimical to welfare state expansion.”

Which brings us back to the filibuster. It’s hard to imagine a legislative rule more clearly designed to “let minority interests obstruct legislation” than a rule requiring a supermajority vote in order to pass ordinary legislation. Eliminate the filibuster, and over time, the United States will become a more generous nation.

The Kristol ball

Once more generous welfare policies take effect, moreover, they become difficult to dislodge — just ask Mitch McConnell, who spent the better part of 2017 engaged in a futile effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

Indeed, Republicans have known for a very long time that they have little hope of unraveling programs like Obamacare once those policies gain a constituency that benefits from them. In a seminal 1993 memo, Republican-operative-turned-#NeverTrumper Bill Kristol warned that “any Republican urge to negotiate a ‘least bad’ compromise with the Democrats” on health reform must be resisted. “Passage of the Clinton health care plan, in any form, would guarantee and likely make permanent an unprecedented federal intrusion into and disruption of the American economy,” Kristol claimed.

Worse, at least from Kristol’s perspective, had President Clinton succeeded in his plans to reform health care, that success would have done permanent damage to the Republican Party.

… its passage in the short run will do nothing to hurt (and everything to help) Democratic electoral prospects in 1996. But the long-term political effects of a successful Clinton health care bill will be even worse–much worse. It will relegitimize middle-class dependence for “security” on government spending and regulation. It will revive the reputation of the party that spends and regulates, the Democrats, as the generous protector of middle-class interests. And it will at the same time strike a punishing blow against Republican claims to defend the middle class by restraining government.

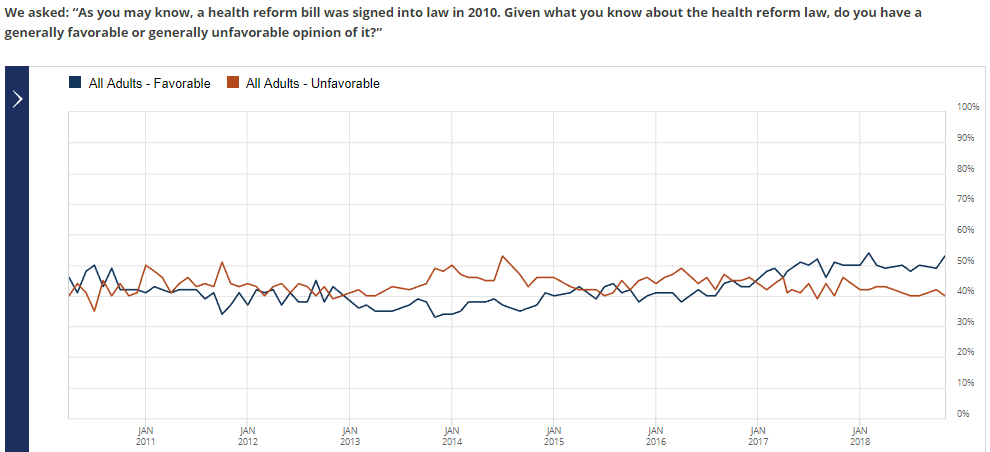

With the passage of Obamacare, Kristol’s fears are now a reality. Democrats just won a crushing victory in an election where voters identified health care as the single most important issue on their minds. And the Affordable Care Act’s approval rating has been on a steady upward trend ever since it took full effect in 2014.

A likely explanation for this trend is a phenomenon known as “loss aversion.” Broadly speaking, humans fear the pain of losing something they already have far more than they enjoy the pleasure of gaining something new. Some research suggests that, you have to give someone two dollars worth of value to relieve the pain they feel from losing a single dollar.

Thus, in 2009, when Obamacare was just a possibility, loss aversion favored the law’s opponents. Rich people were accustomed to paying lower taxes, and didn’t want to lose this privilege. People who already had adequate health insurance feared comprehensive reform because it could leave them without something they already had. There’s a reason why President Obama famously promised that “if you like the plan you have, you can keep it.” He was trying to prevent loss aversion from killing his bill.

Once Obamacare took effect, however, loss aversion worked the other way. Now, people who are insured through the Affordable Care Act have a great deal to lose if the law is repealed. So the law’s opponents face an uphill battle.

The best argument for keeping the filibuster is that it will prevent nihilistic lawmakers like McConnell from gutting existing progressive reforms. But laws like Obamacare already have a powerful inertial force on their side — it’s significant that Senate Republicans were unable to find the votes to repeal the law even when they used the budget reconciliation process which allows bills to pass the Senate with a simple majority.

In the long run, the filibuster does far more to keep good legislation from becoming law than it does to prevent bad legislation from being enacted.

Better voters

There’s one more reason why liberals — and the nation as a whole — will benefit from a filibuster-free Senate. Eliminating the filibuster will lead to better informed voters.

A perennial problem with presidential democracies is that they often leave the voters clueless about who to blame for bad news. Was the slow economic growth of the early 2010s the fault of Democratic President Obama, or of Republicans like McConnell who prevented Obama from enacting his agenda? If America falls into a deep recession before the 2020 election, should we blame Republican President Trump or Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who is likely to prevent Trump from passing controversial legislation?

One of the primary advantages of parliamentary democracy is that it allows one party (or, at least, one coalition) to govern at a time. If Great Britain leaves the European Union, for example, that will happen because a Conservative Party government called for a referendum on Brexit, and because a Conservative-led coalition was unable to negotiate a favorable deal with the rest of Europe. British voters will know exactly who to blame if Brexit proves as disastrous as many experts expect it will.

But in the United States, where presidents of one party frequently share power with legislative majorities from another party — not to mention state governments which might be controlled by either party — there’s no good way for most voters to figure out who to praise for good times and punish for bad times. Elections become contests over tribal identities, rather than informed debates over which party’s policies will benefit specific voters.

Here too, the filibuster contributes to this dysfunction. Even in President Obama’s first two years, when Democrats enjoyed commanding majorities in both houses of Congress, the filibuster enabled McConnell to slow Obama’s agenda to a crawl. After former Sen. Scott Brown’s (R-MA) election reduced the Democratic majority to “only” 59 percent of the Senate, the Republican caucus could block nearly all of that agenda.

The result was that Democrats were crushed in the 2010 election, even though it was Republicans who kept them from meeting the Great Recession with a full-throated response.

The filibuster, in other words, is a Republican’s best friend. Democrats should pray that McConnell is foolish enough to kill it.