By Sam Richards

Residents of Minnesota’s largest county may soon notice police drones whizzing around overhead. The Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office (HCSO) has already deployed a small quadcopter, but what will surprise observers of that drone — assuredly the first of more to come — is the serious lack of oversight regarding its use. Law enforcement officials are able to use the drone to collect evidence without first obtaining a warrant, and they are still failing to explain the full scope of the program.

The quadcopter currently being used in the county was first used as early as May to search for a missing student, according to media reports, despite HCSO officials saying earlier the drone would only begin flying operationally a month later.

The county sheriff’s office maintains that the drone will only be used for search and rescue missions, like the one in May, but it seems that more may be in store. Its Unmanned Aerial Systems policy currently outlines “protocols [for] data intended to be used as evidence” and “[facilitates] law enforcement access to images and data captured by the UAS.”

Such language raises concerns about police surveillance through drones and leaves more questions than answers about a program that has largely remained in the dark.

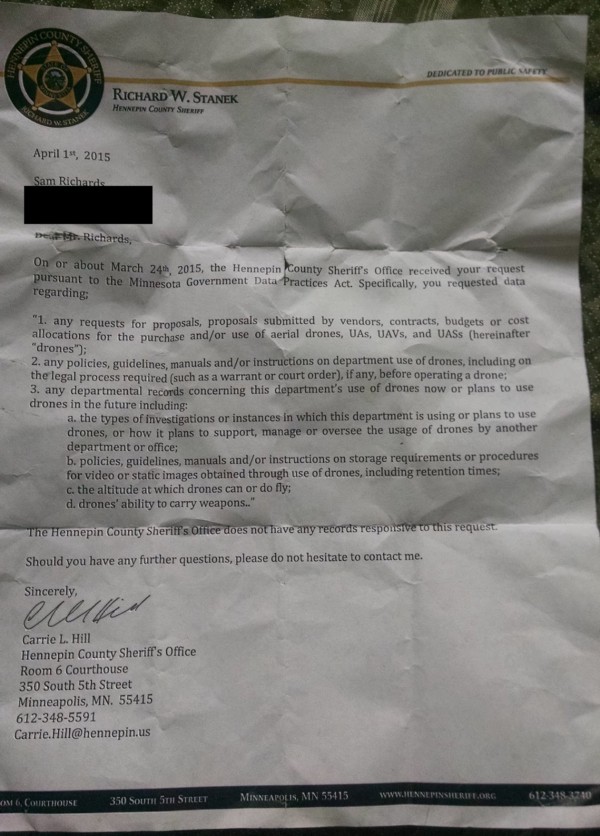

The county has been quiet about the plans it has for the use of drones — blocking public records requests since at least March 2015, claiming at the time that it had no records related to use of drones, plans for acquisition and similar details.

A few months later, Tony Webster, a public records researcher, took HCSO to court over records and emails about its acquisition of biometric surveillance gear. In the documents ordered released by the court earlier this year, several emails from law enforcement lobbyists communicating to law enforcement about their efforts at the Minnesota legislature were made public. These emails not only provided a glance into the shadowy world of domestic militarization and the proliferation of surveillance technology across the United States, but also revealed that the March 2015 drone records request was at least improperly denied, if not willfully obstructed.

In March 2016, after Hennepin County had demonstrated the drone to handpicked observers, the author of this piece filed another public records request for more information, and HCSO finally released its UAS policy, revealing the county’s plans for data collection.

HSCO’s drone policy suggests that incidental collection is likely becoming more common on the local level.

Attempting to question the “protocols [for] data intended to be used as evidence,” and how data collection fits into the declared search and rescue purpose of the drone program, has been fruitless. HCSO has refused to answer repeated media requests through email and phone calls and has also rejected a request for interview.

Perhaps most concerning, the policy stipulates that “data collected by the [drone] not related to an active criminal investigation must be destroyed no later than 30 days,” which sounds eerily similar to incidental collection, a practice whereby innocent individuals get swept into vague and broad searches conducted by law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

It’s already well known that incidental collection happens on a national scale. A four month Washington Post investigation into incidental collection by the NSA, and the files revealed by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, found that “nine of 10 account holders found in a large cache of intercepted conversations… were not the intended surveillance targets but were caught in a net the agency had cast for somebody else.”

Many of the files, the Post reported, “described as useless by the analysts but nonetheless retained, have a startlingly intimate, even voyeuristic quality. They tell stories of love and heartbreak, illicit sexual liaisons, mental-health crises, political and religious conversions, financial anxieties and disappointed hopes. The daily lives of more than 10,000 account holders who were not targeted are catalogued and recorded nevertheless.”

But HSCO’s drone policy suggests that incidental collection, and the serious threat it poses to privacy, is likely becoming more common on the local level as well. And still, there aren’t a lot of details. It’s not clear, for example, if the collected data can be analyzed by the government for possible prosecutions or use it for further investigation before the 30 day limit is up — and the department isn’t being forthcoming.

Lack of warrants for visual aerial surveillance is a hallmark of federal aerial surveillance operations, and a ruling on the police helicopter exemption is used to enforce this on a state level as well. Florida v. Riley (1989) is now used to justify warrantless aerial surveillance across the United States, but it originally considered such surveillance as encompassing only the naked eye of an officer inside a low flying helicopter. The law has not matured with advances in technology, like thermal imaging (which can peer through walls), wide area surveillance (capable of spying on an entire metropolitan area), or any of the other commonly utilized technologies of today. This means the use of drones, without first obtaining a warrant, is actually legal due to the lack of other precedent.

Ben Feist, the legislative director for ACLU of Minnesota, told ThinkProgress that in “exceptional circumstance operations” requiring police agencies to apply for a search warrant even after a drone flight is “too onerous.” For routine patrols, the ACLU tried to meet their counterparts halfway by suggesting law requiring something less than a warrant, such as a court order. That proposal was also rejected by police lobbyists.

For Minnesota, the question lingers: Why would a search and rescue drone need weapons?

This type of exigent circumstances exception is only supposed to be used when it’s dangerous or impractical to obtain a warrant. Effectively, the police in the state want to be able to use their drone uninhibited by procedural processes or oversight. Feist said that the ACLU is concerned that if this precedent is not challenged by new laws, drones could be flying all over the state without appropriate judicial oversight.

Equally surprising, federal law also doesn’t ban police and other agencies from arming drones. And when the Minnesota state legislature tried to put in place stronger judicial oversight for the use of drones, Hennepin County went ahead and deployed the drone before originally planned.

Minnesota Sen. Scott Dibble (D) told ThinkProgress that at a hearing earlier this year, “law enforcement articulated objections to items which were already negotiated,” frustrating lawmakers and stoking feelings that the debate was deliberately sabotaged.

Dibble was a co-author of public safety bill SF 1299, along with Minnesota state Sen. Warren Limmer (R) and former state Sen. Branden Petersen (R). The bill sought to cement into law protections like general oversight of technological acquisitions, mandatory search warrants, requirements for clearly and narrowly defined targets of surveillance, restrictions on the use of facial recognition and other biometrics, timely deletion of data scooped up by drones, mandatory annual reports on the use of these systems, and a ban on arming drones with weaponry.

“Every element of the bill was negotiated with law enforcement and there were compromises,” Dibble said. Shockingly, the law enforcement side also wanted to renegotiate the prohibition of weapons added to police drones, he added. Law enforcement questioned whether or not the ability to fire nets at people, for example, would be ruled out by that provision.

While the quadcopter Hennepin County is currently fielding will probably not be able to handle such customizations, it’s clear that law enforcement does not want to close the door to such ideas. The push against a prohibition of drone weaponization mirrors similar efforts in North Dakota last year. In that case, lawmakers were only able to pass a requirement for search warrants by first legalizing armed drones.

And the limitations on the current drone being used don’t alleviate human rights advocates’ fears of mission creep. A 2011 report from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) noted that even when drones “are being envisioned for search and rescue, fighting wildfires, and in dangerous tactical police operations, they are likely to be quickly embraced by law enforcement around the nation for other, more controversial purposes.” The report included possible future uses of drones, like the “mass tracking” of people or law enforcement intervention, controlling and dispelling protesters by firing tear gas, even deploying weapons.

For Minnesota, the question lingers: why would a search and rescue drone need weapons?

Those keenly aware of the practices of the HCSO have started taking a skeptical look at the department. It wasn’t long ago when law enforcement in Minnesota was criticized for its the use of controversial license plate readers. Similar dissent against the cloak and dagger tactics of police in the state surrounds their use of cellphone spying devices, namely StingRay and KingFish.

To avoid further controversy over its drone policy, HCSO has been incredibly delicate with the public relations surrounding its new tool, carefully wording its messaging in order to avoid detailing the true scope of the drone program.

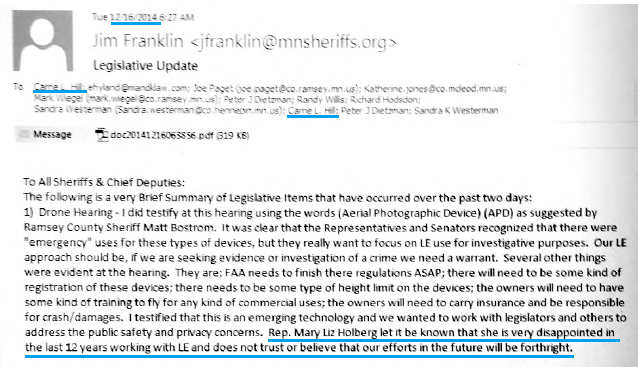

A fine example of this public relations dance was revealed in Webster’s lawsuit. In December 2014, James Franklin, the executive director of the Minnesota Sheriffs’ Association, sent an email to law enforcement officials statewide, including the person who denied the March 2015 drone records request. The email begins with:

1) Drone Hearing — I did testify at this hearing using the words (Aerial Photographic Device) (APD) as suggested by Ramsey County Sheriff Matt Bostrom.

Steering clear of certain terminology is a common tactic early on when military and police forces add advanced technologies and even weapons to their arsenals, in hopes that the public won’t be alarmed by the more innocuous terms. Additionally, public records research can be impeded when an individual submits a request using the wrong wording, even if the intent is understood.

The attempts to avoid oversight, and the clear intent to collect data with the drone, are incredibly worrying for local residents and for civil liberties. There are already serious privacy concerns with the use of private and commercial drones — let alone ones used for law enforcement.

The attempt to block a ban on arming drones with weaponry is similarly troubling, given both the lack of a federal ban and the ways in which other police departments around the country have already used drones. In Florida, for example, drones are restricted from collecting evidence, but can be armed with lethal weapons. And last month, the Dallas Police Department used a robot to kill an active shooter in what the Los Angeles Times said “ushers in a new phase in the militarization of U.S. police departments.”

While these technologies are still new, legitimate concerns due to the lack of oversight with police surveillance technology are only bolstered by deliberate obfuscation by those charged with protecting and serving. Taking advantage of regulatory voids, and the care with public relations messaging around these dangerous tools, should raise even more alarms.

In the words of Dibble, “It’s alarming the total lack of [concern for] civil liberties under the Bill of Rights that these police agencies want to close their eyes to in the use of these drones.”

Sam Richards is an investigative reporter and founder of North Star Post. He focuses on civil liberties and social justice and can be reached on twitter @MinneapoliSam or by emailing Sam@NStarPost.com