The National Football League has spent the last two decades engaging in a extensive cover-up campaign of potential links between its sport and long-term brain injuries, waging war against scientists and researchers who go against it, denying the science those researchers have produced, and misleading players about the effects the game may have on their long-term mental health. That’s the focus of League of Denial, the much-awaited PBS Frontline documentary that stays true to its name in painting a searing, two-hour-long picture of the NFL as Big Tobacco: an industry so hell-bent on making money and preserving its product that it would go to nearly any length to prevent research that shows it may be killing its practitioners from seeing the light of day.

The film, based on the investigative reporting of Mark Fanairu-Wada and Steve Fanairu (they are brothers), details the lengths to which the league went to deny, dismiss, and cover-up possible ties between concussions suffered on the football field and long-term brain injuries, and it leaves viewers wondering what I wondered after reading an excerpt from the Fanairu brothers’ accompanying book of the same name: as the NFL touts the changes its made to address concussions now, why would anyone trust this league — still run by the people who covered up possible connections for so long — to help us answer the questions that still exist about football, concussions, and long-term brain injuries?

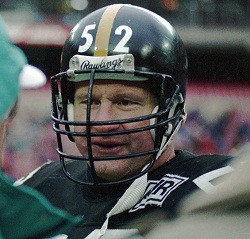

The most illustrative — and damning — moments of the film feature Dr. Bennet Omalu, who discovered chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the disease at the center of this crisis, in an autopsy of former Pittsburgh Steelers Hall of Famer Mike Webster’s brain. Nearly halfway through the film, Omalu, whose published research on the brains of Webster and fellow Steelers lineman Terry Long was publicly dismissed and smeared by the NFL, recounts a conversation he had with an NFL doctor.

“An NFL doctor said to me at some point, ‘Bennet, do you know the implications of what you’re doing?’” Omalu said. “He said, ‘If 10 percent of mothers in this country would begin to perceive football as a dangerous sport, that is the end of football.’”

The NFL, then, had no choice but to squash and discredit not only Omalu’s research but Omalu himself, and that’s precisely what the league did. Omalu left Pittsburgh for northern California, where his work as a medical examiner shielded him from any football-related brain research. “I wish I never met Mike Webster,” Omalu says in the film. “CTE has dragged me into politics of science, the politics of the NFL. You can’t go against the NFL. They’ll squash you.”

Years later, after research into football players’ brains had intensified, the suicide of linebacker Junior Seau motivated Omalu to get back into football-related research. He obtained verbal consent from Tyler Seau, Junior’s son, to examine the player’s brain. The NFL sprung back into action. “According to Tyler, the NFL informed him that Omalu’s research is bad, and that his ethics are bad,” Fanairu said. The NFL’s chosen researchers at the National Institutes of Health later found that Seau indeed had CTE. That was in 2012, 18 years after the NFL had started its Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee, 13 years after its retirement board had admitted a link between football and Webster’s mental disabilities, five years after NFL commissioner Roger Goodell convened a conference of NFL doctors (and left Omalu off the guest list), three years after it heard, in person, a presentation from Dr. Ann McKee detailing the links between football and CTE, a year after Goodell had announced rule changes, overhauled the MTBI committee, and started funneling money into research projects.

For all of the preview portrayals of this film as a vendetta against the NFL — an idea perpetuated by NFL’s lack of participation and ESPN’s decision to end its production partnership with PBS because of its “sensational,” “over the top” trailer — League of Denial explains clearly that there are still questions about what causes CTE in football players and how often it occurs. Despite McKee’s “enormously high hit rate” of finding CTE in former players — McKee has studied 46 brains of dead football players and found CTE in 45 — she admits that full conclusions are limited by a small sample size and a natural selection bias, since the brains she tests come largely from players whose families saw evidence of mental health problems and suspected football as the cause). League of Denial allows doctors who aren’t yet sold that concussions and brain injuries are a football epidemic to freely share their opinions.

But for years, the “questions” about brain injuries and concussions in football were manufactured by the NFL and its doctors, as League of Denial illustrates. And while there are still questions to answer about CTE and football, the intensity of the cover-up and smear campaign is enough to make it obvious that the NFL shouldn’t be trusted with answering them. Yes, the NFL has funded new research and medical examinations and the settlement it reached with 4,500 former players in August requires it to fund even more. But this is still the NFL that went to war against people like McKee and Omalu, a league that published research denying that football was dangerous for the brain, a league that has already decided to backtrack on a previous admission that long-term brain injuries and football had an undeniable connection. It is a league that still employs people like Elliott Pellman, the first chief of the MTBI committee, and still calls Roger Goodell, present in league offices for all of this, its commissioner. It is a league that’s efforts to discredit, conceal, and deny concussion and brain research may be the biggest reason doctors can’t “connect the dots” just yet. It is a league motivated today by the same factors that motivated its original actions.

PBS pitched League of Denial as a documentary that would “change the way you see the game.” Like Alyssa, I’m not convinced it will do that, not with its growing fan base and not in a country where football remains the most popular sport. Still, it ought to be required watching for football fans and parents alike, because if millions of us are going to watch and if millions of us are going to let our children play, we owe it to the men, the children, and ourselves to figure out what that means for the future of the people who play the sport. League of Denial is an important step in understanding the risks those players face. More importantly, it’s an important step in understanding how little the National Football League, a $9-billion-and-growing a year business, cares about learning or publicizing how dangerous the sport really is.