Michigan Republicans are dropping a plan to exempt 17 overwhelmingly white counties from the state’s proposed Medicaid work requirements.

State Sen. Mike Shirkey (R), the bill’s sponsor, told the Associated Press that lawmakers are removing a provision to exempt Medicaid beneficiaries who live in counties with high unemployment, saying it’d be too difficult to administer. Instead, Shirkey said he is drafting a new bill that lowers the hours of work requirements and doesn’t include a similar method of exemption.

Under the original bill, residents in counties with high unemployment wouldn’t have to meet the 29-hour per week work requirements to be eligible for Medicaid. But the way the math worked out, Black communities would be disproportionately targeted by the work requirements, while white, rural residents would be exempt. Shirkey denied that the exemption was effectively racist.

Progressives have cautiously celebrated the move.

“To be honest, all of these types of bills–work requirements for Medicaid, drug testing for welfare benefits, photo ID for voting–have at least a tinge of racism to them no matter what, but at least this one isn’t blatantly racist anymore,” wrote Charles Gaba in his health policy blog ACASignups.

But while what happened in Michigan is good news, it’s worth remembering that the exemption wasn’t unique. Other states around the country are seeking similar exemptions as local lawmakers try to condition insurance on work. And because some states are modeling Medicaid off of their food assistance programs, it doesn’t take much speculation to see the racial redlining at work.

Ohio, for example, is asking the federal government if it could require people on Medicaid to work at least 20 hours a week to receive health insurance — but 26 overwhelmingly white counties don’t have to meet this requirement.

“[W]hile the proposal largely waives employment and community engagement requirements in 26 overwhelmingly white Ohio counties because of their high unemployment rates it fails to exempt other communities with unemployment rates equally high or higher,” said John Corlett, president of the nonpartisan policy and advocacy group the Center for Community Solutions, in a statement. He’s also a former Ohio Medicaid director.

Take the city of Cleveland, for example. As of March 2018, the majority Black city had an unemployment rate of 6.1 percent — higher than Athens county, at 5.1 percent. But Cleveland isn’t exempted from the work requirement because Cuyahoga County’s unemployment rate doesn’t meet the federal exemption. The same is true for majority Black cities like Euclid and Maple Heights. Meanwhile, Athens County, which is 90 percent white, is exempt.

Ohio’s food assistance program operates similarly. In 2013, Ohio exempted residents in 16 majority white counties from having to meet the requirement that they work 20 hours a week to receive more than three months of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. At the time, six other cities, including Cleveland, could have qualified for an exemption but didn’t because of the county they were in. Several advocacy groups filed a complaint with the United Sates Department of Agriculture because the work requirement disproportionately hurt minorities.

“The number of [total SNAP] recipients in waiver counties fell by 3 [percent]. The number of recipients in non‐waiver counties declined 5.6 [percent],” Corlett told ThinkProgress over email, citing data 12 months after the state put the policy change into effect.

“Based on our past Ohio experience, we would expect to see a much faster Medicaid enrollment drop in those communities where people are required to work a set number of hours per month but aren’t living in 26 largely white Ohio counties that the state has chosen to exempt,” Corlett told ThinkProgress.

The federal government hasn’t approved Ohio’s request to add work requirements yet, but if it does residents in these 26 counties don’t have to worry about work rules and the associated paperwork for either Medicaid or SNAP, as the exemptions are drawn up in a similar way.

A similar situation is playing out in Kentucky, where work requirements go into effect in July.

Kentucky officials sought work exemptions for SNAP beneficiaries since 2009, but started to let them expire in 2016, finishing off in May 2018, in every county except eight: Bell, Clay, Harlan, Knox, Leslie, Letcher, Perry, or Whitley. These are majority white, rural counties — and they’ll also be exempted from the 80 hours per month Medicaid work requirement until 2019.

The requirement was initially slated to roll out in the northern Kentucky region first, which includes Jefferson County where a larger share of Black Kentuckians live. But this has changed. Kentucky’s rule will roll out beginning with Campbell, Boone, and Kenton counties in July. But the state still isn’t accounting for factors that could influence whether or not people meet the requirement, said Dustin Pugel, a Policy Analyst at the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.

“It is the case though that you know there are higher rates of unemployment among black Kentuckians and… there are racial discriminations in the workforce that they have to contend with that white workers don’t have to contend with,” Pugel told ThinkProgress. “It’s also true that based on the flaws in our criminal justice system that black workers or black Kentuckians in general have a higher rate of criminal records. And so it is harder for folks with a criminal record to get a job and there’s no built in exemption for that.”

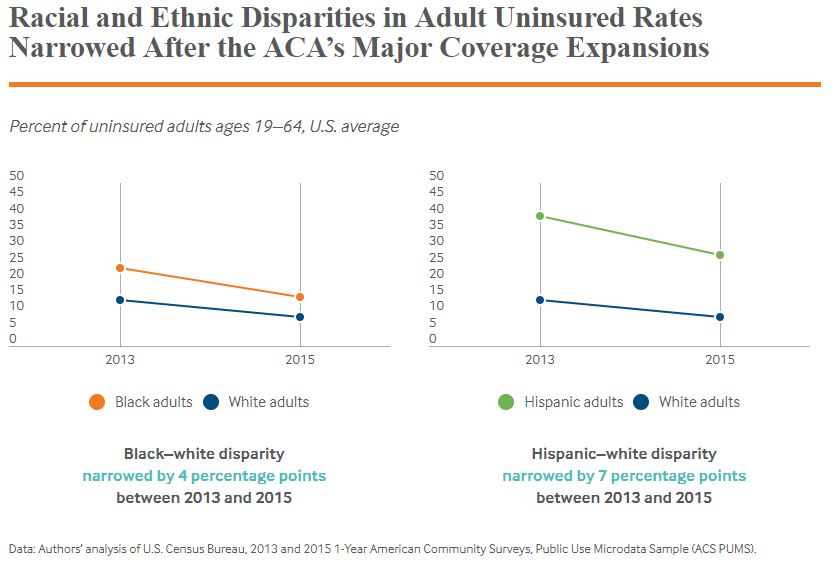

These sorts of exemptions are especially concerning given the progress that has been made in addressing racial disparities in health care.

Disparities among racial and ethnic groups in health care access narrowed under the Affordable Care Act, particularly with Medicaid expansion. Work requirements could undermine this.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that SNAP waivers expired in 2016 for the eight named counties; in reality, they began to expire that year. This piece has also been updated to further clarify how the SNAP requirements are rolling out in northern Kentucky.