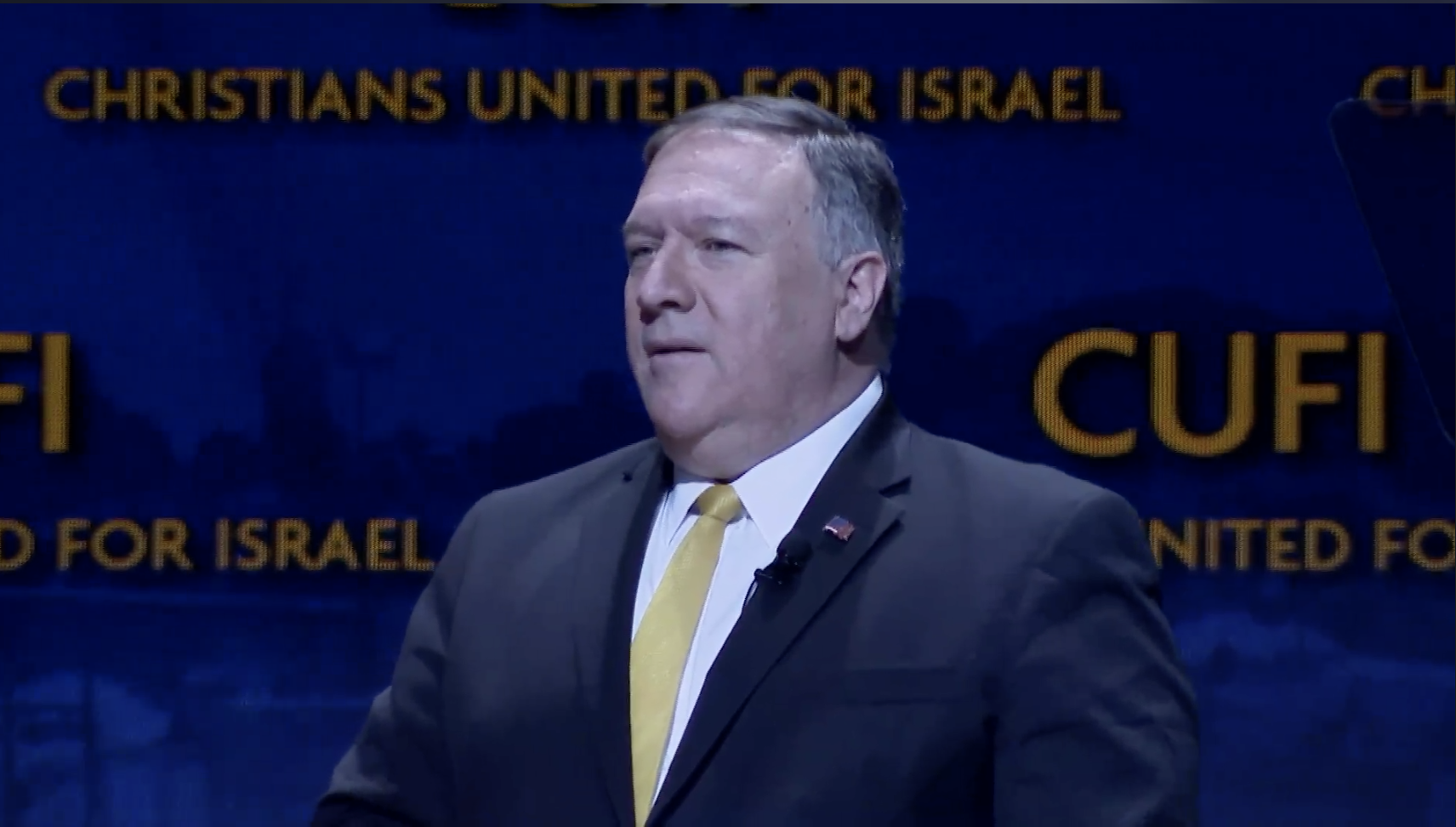

Speaking at the Christians United For Israel event in Washington, D.C., on Monday, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo threatened that the Trump administration is “not done” with Iran.

“We’ve implemented the strongest pressure campaign in history against the Iranian regime and we are not done,” said Pompeo, adding that U.S. sanctions have deprived Iran of funds it would have used “to destroy the state of Israel.” (Iran has never been at war with Israel.)

“You know, a lot of people get spun up in the wrong ideas that American evangelicals want to impose a theocracy on America,” said Pompeo, laughing. “I wish they’d been concerned about the real theocratic takeover that has been happening in Iran for the last four decades,” he added.

If Pompeo’s comments about Iran seem bizarre in the context of a speech about evangelicals, the timing was no coincidence. They came hours after Iran announced that it exceeded the enrichment limit of 3.67% in the 2015 nuclear deal agreed upon by Iran, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Russia, and China. President Donald Trump violated this deal last year when he withdrew from the agreement and reimposed sanctions on Iran.

According to Iranian news agencies, Behrouz Kamalvandi, spokesman for Iran’s nuclear agency, said that Iran is now enriching at 4.5%, useful only for energy purposes. (Iran does not have a nuclear weapons program.)

He also told state television on Monday that the country might increase its enrichment to 20%, which an be used for research or medical purposes. In order to have enough material to build a bomb, Iran would have to increase its enrichment to 90% and sustain that production for a year.

In upping its enrichment, Iran did exactly what it said it would do weeks ago, though at the time, Kamalvandi said Iran might go up to 5% to meet the needs of its reactor in Bushehr.

Since President Trump pulled the United States out of the deal in May 2018, he has reimposed sanctions on Iran and threatened secondary sanctions on other countries that invested in or traded with Iran.

The Trump administration has issued a series of demands on Iran that deal with concerns outside the nuclear deal — such as the country’s ballistic missile program and involvement in Syria’s civil war. The changes essentially require Iran to change its entire foreign policy and set aside key aspects of its own national security.

While Trump has said that he is open to meeting with Iranian leadership to negotiate a new deal, Iran has repeatedly said that it will not do so until the United States rejoins the deal and lifts the crippling sanctions it has imposed on a country of 80 million.

“It should not be a surprise to anyone that after putting forth an effort to stay in compliance in spite of U.S. sanctions, Iran has gotten to a breaking point in terms of their own politics [and needs to] take actions to test to see whether in fact there’s a way forward here or not.”

The obvious question, of course, is this: Why should Iran negotiate with an administration that might be out of the White House in less than two years? Brian Hook, the U.S. special envoy on Iran, essentially mocked Iran for bothering to agree to the deal with President Barack Obama when he had less than two years left in office.

“It’s disingenuous for the Iranian regime to say that they can’t trust this administration because we left the deal. They knew what they were getting into when they negotiated a deal with a president who had about a year and a half left in office,” said Hook in a June 24 press call from Oman.

Ambassador Wendy Sherman, former U.S. lead negotiator on the Iran nuclear deal and former Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, told ThinkProgress that throughout the negotiation, Iranian counterparts pressed this issue, essentially asking: “‘How do we know that this is going to last,’ knowing that we had an election coming. And I said, ‘How do we know that it will last on the Iranian side?'”

Sherman, speaking on a press call on Monday morning, pointed out that Iran too, has politics.

“So what I said, constantly…to our interlocutors was, ‘This will be durable depending on how good of a deal it is.’ And the fact that it stayed durable for a year, even after the United States, who has the most consequential and far-reaching sanctions put back in place, is a testament to the strength of the deal itself and the mechanisms in it,” said Sherman, now a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School.

But no deal is “sacrosanct” or “forever.” And, indeed, from the Iranian perspective, the deal has been far from durable.

“It should not be a surprise to anyone that after putting forth an effort to stay in compliance in spite of U.S. sanctions, Iran has gotten to a breaking point in terms of their own politics [and needs to] take actions to test to see whether in fact there’s a way forward here or not,” she added.

The fact that the Trump administration left the deal, said Sherman, puts its credibility “in greater question.”

Robert Malley, who was also a negotiator on the Iran deal, said that Iran would clearly want any new negotiation to be multilateral, not only because of the lack of trust in the Trump administration, but also because it would bring the other parties to the deal — who still support it — back into the room.

But, Malley, currently the president and CEO of the International Crisis Group, added that “President Trump doesn’t believe in multilateralism. He won’t want to replicate the format that President Obama initiated. He doesn’t have much trust at all in the Europeans.”

So how any talks will proceed will depend greatly on whether Iran and the United States can overcome their mutual mistrust and possibly work with a third party to pursue a path forward.

The United States also stopped granting waivers to countries taking shipments of enriched materials and heavy water from Iranian reactors, which virtually guaranteed that the country would surpass the 660-pound limit on stockpiles of enriched materials.

In announcing that Iran would enrich uranium to any amount it wanted, President Hassan Rouhani last week advised European partners and the United States to “go back to logic and to the negotiating table.”

Less than 48 hours after that statement, the U.K. seized a ship carrying Iranian oil to Syria off the coast of Gibraltar. While selling oil to Syria is a violation of European Union sanctions put in place in 2011, since the start of the uprising/civil war in Syria, no Iranian ship had been seized for doing so.

Iran denies that the oil was going to Syria, as has been reported, and essentially accuses the United Kingdom of doing the bidding of the United States. Indeed, the seizure of the tanker was immediately applauded by U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton, who called it “excellent news.”

Bolton has also supported military escalation in Iran, blaming a series of oil tanker attacks on Iran (a charge the country denies).

Since May, the Trump administration has sent a U.S. carrier to the Gulf as well as bomber jets. When Iran downed an unmanned U.S. surveillance drone it said was in Iranian airspace (the U.S. claims it was not), Trump said he ordered a series of military strikes on Iran before canceling the mission 10 minutes prior to execution.

Since then, things have been quiet, if tense, in the region. Trump has warned that Iran “will never have a nuclear weapon”, even though the country has always insisted that it does not want one. He has also tweeted that the threats to increase enrichment will come back to “bite” Iran “like nobody has been bitten before!”

The increase in enrichment limits is largely seen as a tactic to pressure European partners to deliver what was promised under the nuclear deal: Sanctions relief that would allow Iran to regain access to the global economy community, in trade, development, and banking.

The steps Iran has taken are reversible, but so far the Europeans have not found a way to make good on what the deal promised and avoid secondary U.S. sanctions.