The White House convened a summit on the opioid epidemic Thursday, where drug addiction experts and victims asked Trump administration officials about what was being done to curb a crisis that kills an average of 115 people nationwide every day. People harmed in some capacity by the epidemic spoke directly with cabinet secretaries, but there was a noticeably absent voice: those of people of color.

The lack of racial diversity is an increasingly obvious trend in the Trump administration, and particularly with regard to its health agenda. The administration rarely, if ever, gives people of color a platform to speak about their troubles under Obamacare and has, instead, targeted programs that disproportionately help minorities. Moreover, the opioid summit’s lack of diversity is especially troubling given the United State’s troubled history with drug policies that have devastated Black and brown communities.

Officials within the Trump administration took the opportunity to highlight its “compassionate” approach to the opioid epidemic. The exception to this was President Donald Trump, himself, who suggested, instead, that the death penalty be used on drug dealers. The secretaries highlighted current treatment and educational efforts underway, and there was only one mention of Trump’s border wall — a policy he argues will keep drugs out. (Although, experts say the wall won’t really help.)

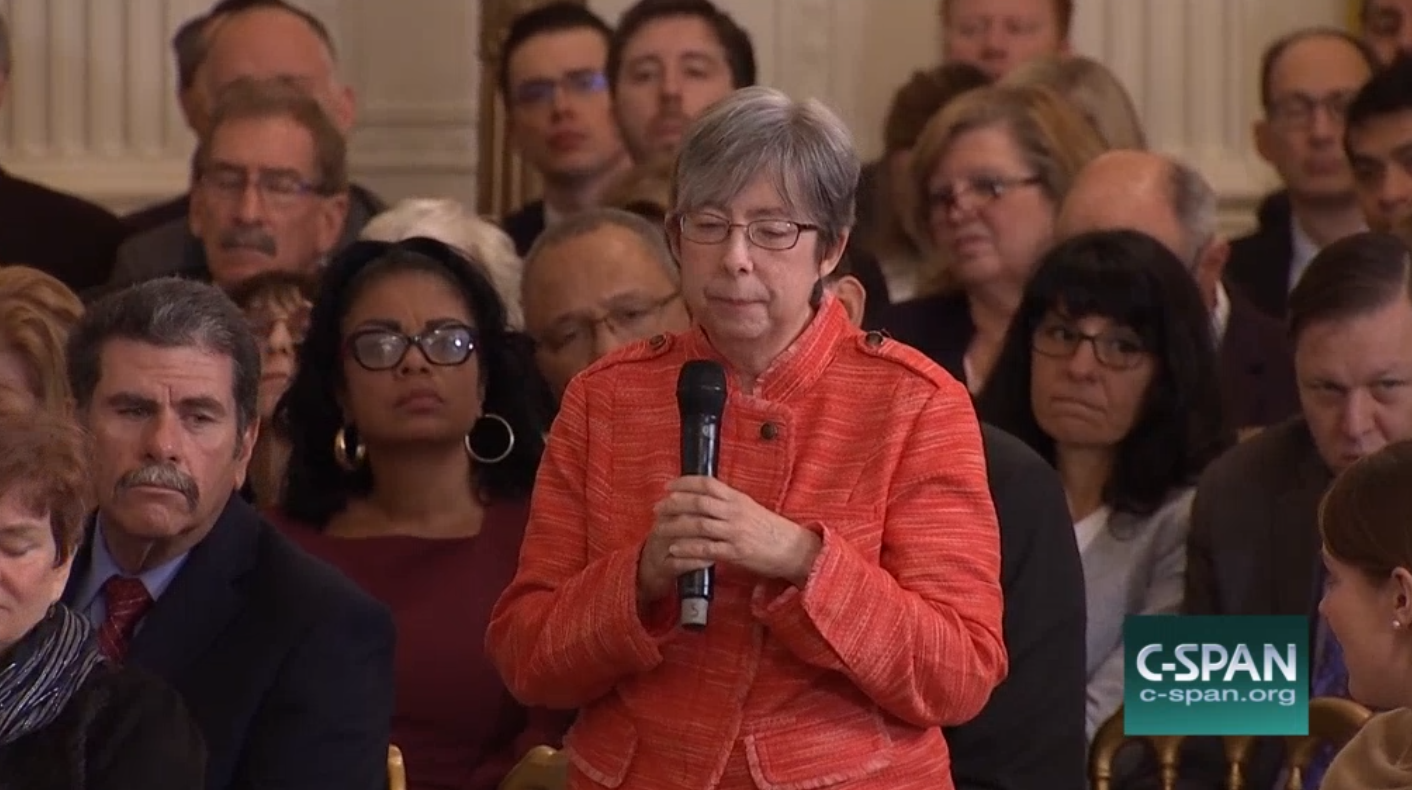

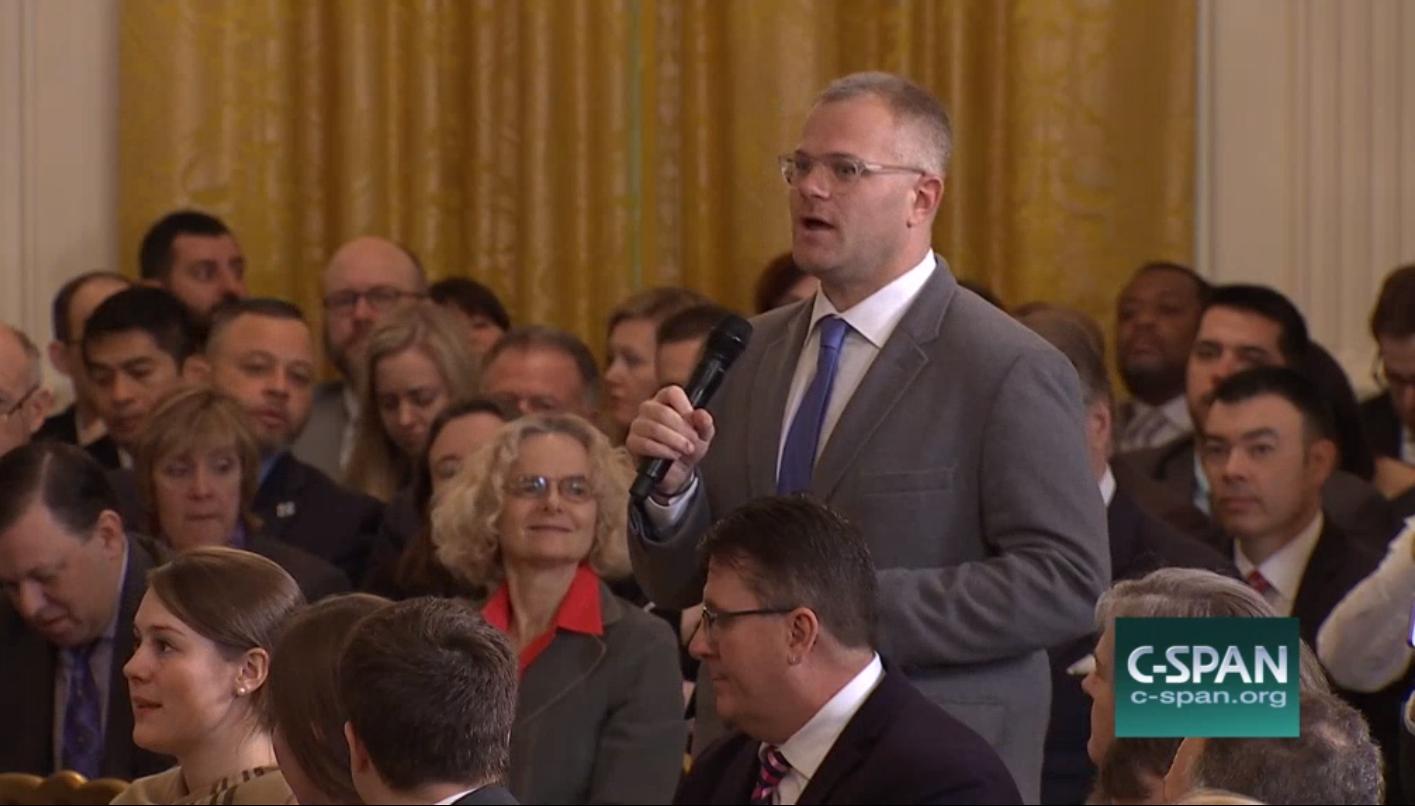

The summit was broken up into three parts. The first featured cabinet secretaries from the federal Health, Veterans Affairs, and Housing and Urban Development departments. Seven people asked questions — some in recovery, others who are doctors, many who traveled long distances from Pasadena, California, to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania — and all were white. Jim Carroll, the president’s pick for Drug Czar briefly spoke afterwards, and didn’t answer questions. In the third and final panel, five others were able to ask the attorney general and Homeland Security and State officials questions, and only one was a person of color — Dr. Janette Nesheiwat, who’s Jordanian-American.

This is not to say that Thursday’s conversation wasn’t substantive, but that the Trump administration omitted a critical voice, further whitewashing an epidemic that impacts nearly everyone. While the common narrative is that drug overdoses exclusively impact white residents, recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows drug overdose deaths are skyrocketing among Black Americans. In fact, this community is now dying at about the same rate as the white community did in 2014. In some cities, like Chicago, opioids are killing Black people at a higher rate than white people.

There were some Black and brown faces in the audience and Ben Carson, the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, was among the panelists speaking, but overall, diversity was dismal. When ThinkProgress reached out to the White House for comment, the administration emailed a press release with a list of notable individuals who were invited. One person of color — Dr. Monty Burks, the director of faith-based initiatives at the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse — was highlighted in the White House press release.

It is especially important that public officials elevate Black and brown voices because of the country’s past regressive drug policies that have negatively impacted people of color. Now that the United States rightfully calls this epidemic a public health crisis, and not a “War on Drugs,” it is especially critical to invite all voices and stakeholders to the table. This is especially important because while opioid addiction isn’t racist, treatment can be.