After the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) and Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) projects were proposed almost five years ago, residents in rural western Virginia fought hard to persuade state and federal regulators to reject the companies’ requests to build the pipelines through their communities.

When regulators gave the two massive construction projects green lights to proceed almost a year ago, the residents didn’t concede defeat. They grew even more determined to stop the pipeline construction in its tracks.

After the MVP was approved in October 2017, “we decided that we weren’t going to sit by idly and let them run over us with their construction equipment,” Kirk Bowers, pipeline program coordinator for the Sierra Club of Virginia told ThinkProgress. Bowers is one of the leaders of Mountain Valley Watch, a group created to monitor construction of the pipeline.

Residents have signed up to serve as volunteer monitors and scouts for what have essentially become citizen regulatory agencies. Mountain Valley Watch was formed earlier this year as was the Pipeline Compliance Surveillance Initiative (Pipeline CSI), which is keeping a close eye on the the ACP.

The dual monitoring efforts involve hundreds of volunteer observers and collaboration with environmental organizations and citizen groups — such as Friends of Nelson County and Augusta County Alliance — formed years ago to protect the property rights, rural heritage, and environment of the region.

In some cases, these volunteer monitoring groups have gathered more information on the pipelines’ impact on the environment and private lands than the regulators that are paid to monitor the projects.

The mission of these all-volunteer oversight groups is to make sure laws are obeyed and no corners are cut during construction. And if the volunteers do their jobs well enough, they hope to provide enough evidence of violations to force regulators to issue permanent stop-work orders on the projects.

The monitoring groups have put in place systems that allow rapid response by water quality experts. Residents who live near the pipeline paths, for example, can use websites to submit online incident reports or call into a telephone hotline about a potential construction violation. They also can view interactive pipeline websites if they need location information.

“We dispatch first responders to look and get photographs and collect water data in response to an incident report,” said Rick Webb, coordinator of the Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition (DPMC), a group of volunteers organized to make sure Dominion Energy is following the law in its construction of the ACP.

Founded in 2014, the DPMC is an organization of citizen volunteers, conservation groups, and environmental scientists that came together in response to Dominion’s proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline, which will cross the George Washington and Monongahela National Forests and the adjacent mountains and valleys.

Earlier this year, the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance, of which the DPMC is one of its more than 50 members, formed the Pipeline CSI, to ensure strict application of environmental laws and regulations during construction of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. The Pipeline CSI program — intentionally named after the television series in which investigators search for physical evidence to solve crimes — has hundreds of volunteer observers in Virginia and West Virginia who work closely with environmental organizations.

“We literally are trying to do the regulatory agencies’ jobs for them,” said Webb, a retired senior scientist with the University of Virginia who also serves as committee chairman of the Pipeline CSI.

Planes, drones, and first-responders

Groups such as the Pipeline CSI and Mountain Valley Watch use drones to monitor the pipeline routes. They also have airplanes — known as the Pipeline Air Force — that are equipped to take thousands of photographs on each trip. The cameras shoot straight down from the airplane every second. Volunteers are trained to examine the photos to determine whether a potential construction violation is occurring.

The pipeline monitoring groups also have access to a network of water quality experts who go out and analyze potential construction damage to streams and other bodies of water using high-end instrumentation.

According to Webb, state and federal agencies don’t have the political will to do an adequate job protecting the hundreds of streams crossed by the two pipelines.

“The agencies are understaffed and, in any case, very reluctant to inconvenience the pipeline companies,” Webb said.

Dominion is the largest economic force in the region and donates huge amounts of money to the Virginia General Assembly. The company, Webb said, has an “outsized influence on how things are done in Virginia.”

Dysfunctional regulatory review process

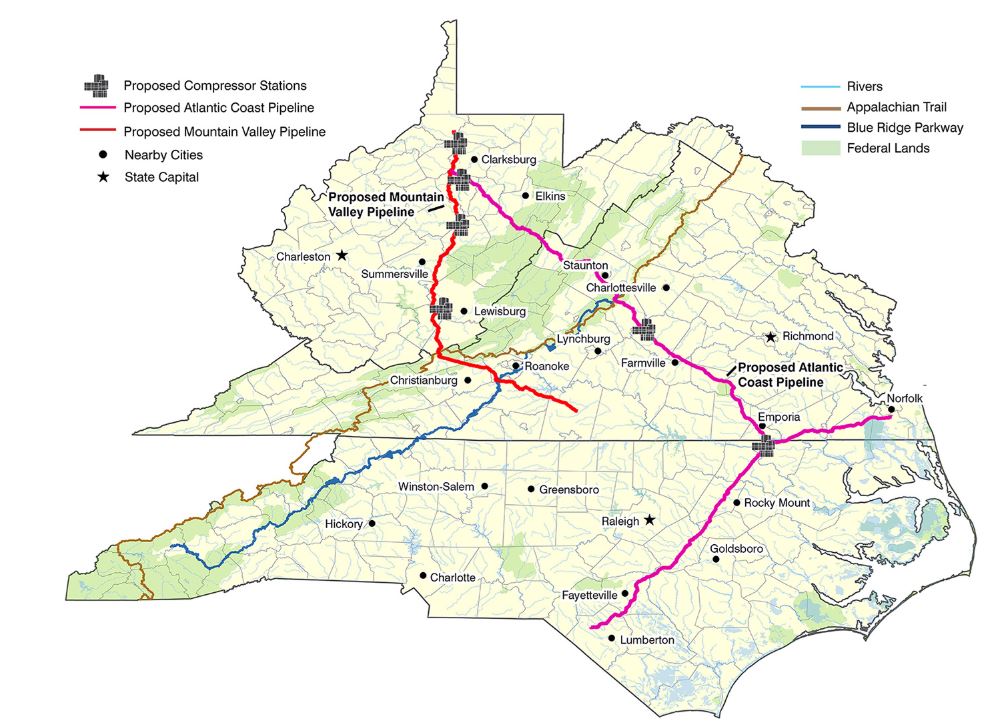

The $5.1 billion ACP, led by Dominion Energy, would be a 42-inch-diameter gas transmission system originating in Harrison County, West Virginia, and running 550 miles into North Carolina.

The $3.5 billion MVP, a partnership headed by EQT Corp., would start in West Virginia and travel south of Roanoke, Virginia, and interconnect with the Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line system at a compressor station in Pittsylvania County, Virginia. A 70-mile expansion of the 42-inch-diameter pipeline into North Carolina has also been proposed as part of the project.

Both pipelines would transport natural gas produced in the Marcellus and Utica shale regions in northern West Virginia and southwestern Pennsylvania for use by power plants and residential, commercial, and industrial end-users — and possibly as exports to foreign markets.

It’s been a “dysfunctional regulatory review process” ever since the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and state agencies such as the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) received the applications for the two projects, according to Webb. FERC and the state agencies failed to do “reasonable environmental reviews” and have been willing to waive basic requirements, he said.

In the latest concession by state regulators to the pipeline developers of the MVP, the Virginia State Water Control Board on August 21 voted to decline calls from environmental groups and landowners to reconsider important water-quality permits for the MVP and ACP, despite major environmental violations committed by the developers of the multi-billion-dollar projects.

The lack of proper regulatory reviews by federal and state regulators is what many believe is allowing opponents of the two pipeline projects to find success in the courts. “It’s these agencies short-circuiting the review process that’s giving us traction in the courts,” Webb said. “They’re not complying with the laws and regulations and precedents that are in place.”

Earlier in August, FERC ordered a halt to construction on the ACP following a federal appeals court decision to reject construction certificates that had been approved. The agency issued a similar stop-work order earlier this month for the MVP. Both orders followed decisions issued by the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, based in Richmond, Virginia.

According to the court, the National Park Service should not have issued a permit to allow the pipeline to tunnel under the federally owned Blue Ridge Parkway because the park service failed to explain how the pipeline fit with its mandate to conserve public lands. For its part, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a permit to Atlantic Coast Pipeline without properly assessing the pipeline’s impact on threatened wildlife.

Dominion Energy and EQT Corp., the primary sponsors of the two pipeline projects, did not respond to requests for comment from ThinkProgress at the time this article was published.

Webb said the Pipeline CSI documented that about 7,900 feet of pipe was newly placed in the pipeline corridor between August 5, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit vacated the two construction permits, and August 12, when FERC issued its stop-work order.

Dominion Energy is arguing that it should be allowed to bury much of this pipe. However, pipeline opponents argue that it should be removed from the corridor because Dominion was ignoring the court’s intent in its August 5 decision when it deployed the pipe.

For the MVP, the court on June 21 invalidated a water crossings permit issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and halted all construction in streams and wetlands in West Virginia. A month later, the court vacated two more of the MVP’s federal permits. These were related to construction within the Jefferson National Forest. FERC ordered all construction to halt following that ruling.

According to Webb, employees at the various agencies have told him — off the record — that the monitoring work of the Pipeline CSI has been helpful.

The Virginia DEQ had not responded to a request for comment from ThinkProgress at the time this article was published.

Volunteers go where regulators don’t tread

Several cases of erosion and sediment runoff have already plagued construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline in southwestern Virginia only a few months into its construction.

With on-the-ground monitoring and aerial surveys of the pipeline routes, volunteer groups have discovered potential violations they believe would have gone undetected if they had not volunteered to do the work themselves.

“Every time it rains, mud comes flowing down off the mountainsides and hills into streams,” said Bowers, a licensed professional civil engineer who has worked as a private contractor and in state government. “DEQ can’t get in there to observe them. The only way they know these violations are happening is because we’re out there in the field doing the work.”

Construction of the 303-mile Mountain Valley Pipeline entails clearing 125-foot rights of way along mountainous terrain and then digging ditches to bury the 42-inch diameter pipe.

The terrain through which the developers are building their pipelines is steep and hard to reach. Through the years, state highway departments have refused to build roads through the region due to its rugged nature.

For the MVP, the Virginia DEQ has used minimal staffing to inspect the project. Three full-time employees and three part-time contractors have been assigned to the portion of the MVP currently under construction, according to Bowers. “That’s not enough. We’ve told [Virginia DEQ Director] David Paylor that they they are over-extended on their construction area.”

Bowers spends much of his time traveling through western Virginia, training volunteer monitors. He meets with residents who have formed groups in opposition to the pipeline in Giles, Montgomery, Craig, Roanoke, and Franklin counties, Virginia.

Bowers usually gets a big turnout for his training sessions. A deputy sheriff in Franklin County came to a session on his personal time because he wanted to learn how to spot erosion problems. Overall, the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office has been “very friendly” to opponents of the MVP, Bowers said.

So far, the efforts of Mountain Valley Watch have generated more than 150 reports of violations to state regulators in Virginia.

Both the ACP and MVP will be crossing hundreds of streams and waterbodies, a major concern for clean water advocates. “These two pipelines are easily the greatest threats to water quality in Virginia in the time that I’ve worked in the environmental field, and that’s about 40 years,” David Sligh, conservation director for Wild Virginia and an investigator for DPMC, told ThinkProgress.

So far, only tree-cutting has occurred in Virginia in preparation for construction of the ACP. But volunteers are already in place along the path of the pipeline once construction crews move from West Virginia into Virginia.

“We have a crew of experts who have been trained and are still being trained on how to use certain kinds of monitoring equipment,” he said. These monitors will document problems that Sligh says will be “evidence grade,” or strong enough, with sound scientific results, to use in court.

When the volunteers find sediment runoff or other potential violations, they write up incident reports and send them to the appropriate government agency. When the complaints are filed, the volunteers cite the legal codes and regulatory requirements, making it easier to take legal action against the pipeline developers, if needed, in the future.

Pipeline CSI program serves as model

In North Carolina, environmental groups are recruiting volunteers to serve as citizen scouts for that state’s portion of the ACP. Like their counterparts in Virginia, the group, called N.C. Pipeline Watch, will train the volunteers to spot environmental violations that could lead to fines or work interruptions.

Almost 200 miles of the 600-mile-long ACP will travel through eastern North Carolina. Construction of the ACP threatens nearly 326 different waterbodies and at least 468 acres of wetlands in North Carolina, according to estimates by the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“It’s clear to me that this is the model that has to be developed if we’re going to have any chance of preserving what’s left of environmental integrity,” Webb said.

This summer, the Sierra Club helped launch the initiative in North Carolina to ensure the ACP “doesn’t get away with violating the commonsense environmental protections that keep our air and water clean,” Kelly Martin, director of the Beyond Dirty Fuels Campaign for the Sierra Club, said in an August 1 statement.

The North Carolina Pipeline Watch is modeled on the Pipeline CSI, the Virginia program that uses volunteer observers and local residents to find suspected regulatory compliance violations. The other organizations involved in the North Carolina Pipeline Watch include Sound Rivers, Winyah Rivers Foundation, and Cape Fear River Watch.

“Our volunteers will be watching the project carefully, reporting violations in an effort to protect our waterways and hold the ACP accountable,” said Kemp Burdette, who serves as the Cape Fear Riverkeeper.

Sierra Club, Sound Rivers, Winyah Rivers and Cape Fear River Watch volunteers and staff will monitor the Atlantic Coast Pipeline construction activities for violations of environmental protections required by state and federal permits. https://t.co/Ldbfk85Xk0

— Coastal Review Online (@Coastal_Review) August 3, 2018

Despite the major troubles faced by MVP construction crews, the Virginia DEQ has issued only one notice of violation against the pipeline project. In West Virginia, the MVP already has received four violations from state regulators regarding failure to implement erosion control solutions.

Webb said the notice of violation issued by the Virginia DEQ is “a slap on the wrist” that will represent a “very small part of the cost of doing business.”

With previous construction projects, inspectors with the Virginia DEQ would, as Webb described, apologetically tell pipeline construction crews that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was forcing them to keep close tabs on their work. “Everybody blamed the EPA” for making everyone do extra work, Webb said.

With the creation of the Pipeline CSI, “they can blame us,” he noted.