From her eastern Washington home, where she has lived for the past 10 years, Robin Priddy has seen firsthand the consequences of climate change.

“Over here, in the eastern part of the state, the past couple of years have been beastly in terms of wildfires, and we perceive that as definitely having a connection to climate change,” Priddy said. “So the notion of doing something about it, we feel pretty strongly about it.”

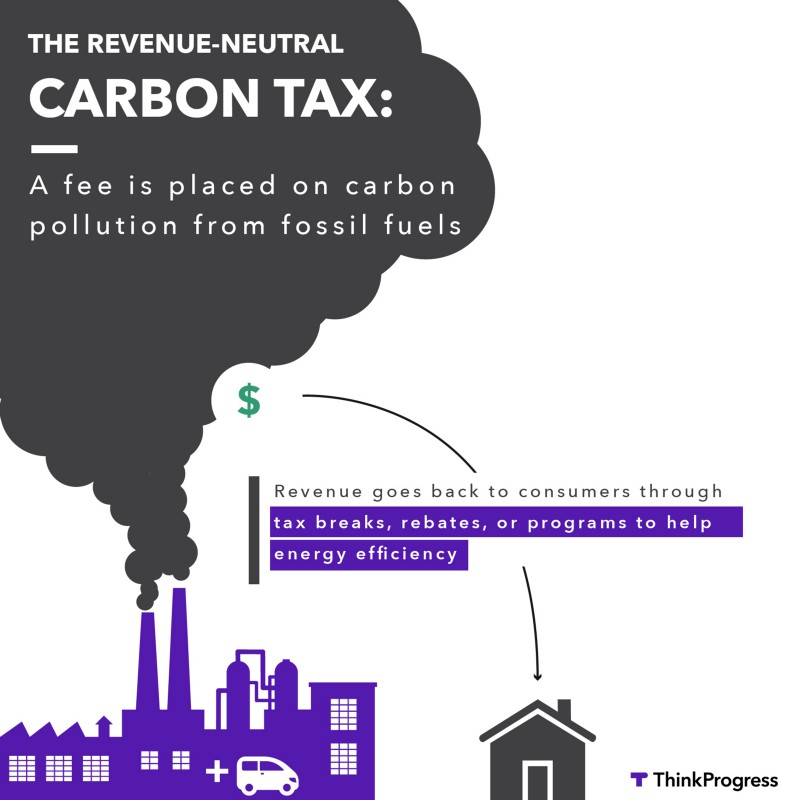

This November, Priddy will have the rare chance to vote on whether the state should tackle climate change by going after the root cause: rampant atmospheric pollution of greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide. Washington residents will be presented with the choice to implement a statewide price on carbon — the only such measure on ballots this fall. Initiative 732, modeled after the successful — and widely popular — carbon tax in British Columbia, would place an initial $25 tax on a metric ton of carbon dioxide, and then use that money to fund both tax cuts and tax rebates throughout the state.

On paper, Initiative 732 has a lot going for it: CarbonWA, the grassroots group behind the initiative, argues it’s revenue-neutral, would cut down on carbon pollution, and would make the state’s notoriously regressive tax code — the most regressive in the entire country — more progressive. Christopher Knittel, professor of energy economics at MIT, has called it “by far the most aggressive U.S. proposal” he’s ever seen. Plus, it’s earned the support of current and former lawmakers, including several Republicans.

“The notion of doing something about [climate change], we feel pretty strongly about it.”

The grassroots team has also managed to out-raise industry opposition to the initiative almost five to one, bringing in more than a million dollars to the opposition campaign’s $260,000. Fossil fuel companies have been surprisingly quiet, with big utilities like Puget Sound Energy and PacifiCorp donating just $25,000 and $10,000, respectively, to the opposition campaign.

And yet the path to a carbon tax in Washington remains uncertain for backers of Initiative 732. Despite the relatively subdued opposition from Republican lawmakers and fossil fuel interests, CarbonWA and its supporters face much louder — and, perhaps, more damaging — criticism from within the environmental movement.

In a move that came as a surprise to many, long-standing and well-respected groups like the Washington Environmental Council and the Sierra Club chose not to support the bill. The initiative, they argue, doesn’t go far enough to protect the communities most at risk from the impacts of climate change and environmental pollution, nor does it help spur the kind of massive reorganizing of energy and transportation infrastructure needed to fight climate change. The nation’s most aggressive price on carbon, they argue, simply isn’t enough.

It’s a sharp contrast from traditional climate debates, which often center on the basic question of whether climate change is a real, man-made phenomenon. The debate over Initiative 732, which has raged for more than a year within the Washington environmental community, and, more recently, in the public spotlight, seeks to answer a more difficult question: not whether we should act to slow climate change, but how exactly we should do it.

Yoram Baumann, the environmental economist behind CarbonWA and Initiative 732, is, in many ways, neither your typical environmentalist nor your typical economist. That’s due in large part to a few crucial revelations that shaped Bauman’s life trajectory: First, as a math student at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, he became fascinated with the idea of environmental tax reform, a concept that argues for shifting the tax burden away from things like income and employment taxes and onto things like pollution. In the mid-1990s, this was still a relatively untested theory — implemented only in a handful of European countries — but Bauman was immediately struck by the concept, which he described, years later, as “an intellectually beautiful idea.”

Then, in the early 2000s, while living in Seattle and working towards his PhD in economics, Bauman got into stand-up comedy to, as he tells it, “blow off steam.” His big break into the world of stand-up came when he wrote a parody of Mankiw’s Ten Principles of Economics. The video got over a million hits on YouTube, and Bauman began touring the world as the “first and only stand-up economist.” Today, he pays the bills with his professional stand-up career.

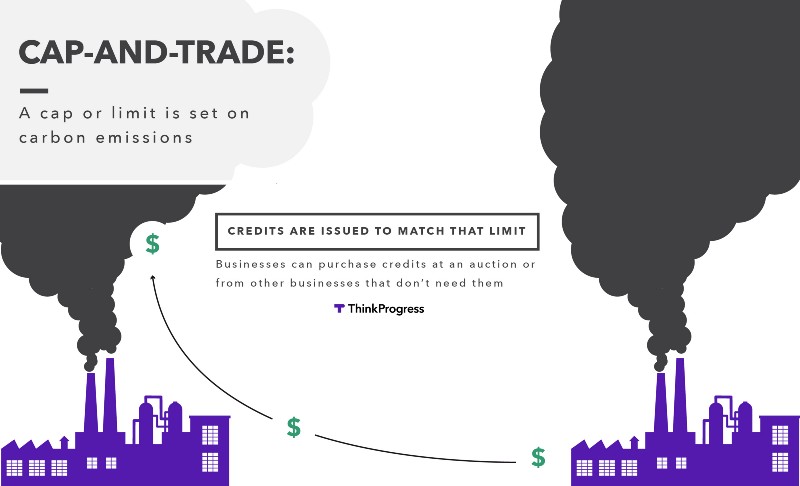

But the idea of environmental tax reform never ceased to interest Bauman, particularly in the form of a revenue-neutral carbon tax, which returns all the revenue generated from the tax back to taxpayers. In 2009, Bauman watched as the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill failed to make it out of Congress, and decided that climate action — which in his mind, meant environmental tax reform — would need to happen at a local level. So he created CarbonWA, a grassroots organization dedicated to pushing a revenue-neutral carbon tax in Washington state.

The group started small, consisting mainly of Bauman and a handful of University of Washington students he met as a lecturer. During the 2014 midterm elections, which saw an unprecedented amount of money funneled to pro-environment Democrats, the group tried to launch a ballot initiative for a revenue-neutral carbon tax. That effort failed but, undeterred, they regrouped, hired some paid staff, and prepared to take another swing at the ball in 2016.

The main goal remained moving climate action forward, in a meaningful way, in Washington state. And again, Bauman and the team at CarbonWA teed up a revenue-neutral carbon tax that would levy a $25 per metric ton price on carbon dioxide — about equal, if a little below, the federal government’s Social Cost of Carbon — and recycle the revenue back to taxpayers in three specific ways: by lowering Washington’s statewide sales tax by 1 percent, by funding and increasing the state’s unfunded 10 percent match of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, and by effectively eliminating the state’s business tax for manufacturers.

To Bauman and his colleagues at CarbonWA, the initiative seemed like a win-win, something that would drive down carbon emissions while moving Washington’s notoriously regressive tax code — the worst in the entire country, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy — forward. The group worked with economists at the University of Washington to calculate the financial impact of the carbon tax on the average taxpayer, and found that most households would end up either paying or earning between $100 and $200 each year in a state that takes in about $5,000 in taxes per household annually.

“In general, because a sales tax is even more regressive than energy taxes, if you use the revenue generated to reduce sales tax it then becomes a progressive policy,” MIT’s Knittel said of the proposed carbon tax.

Bauman can list a number of reasons why he and his team felt this was the best approach. A carbon tax, he argues, is simple and transparent, and can kick in immediately, unlike a cap-and-trade system, which can take years to set up. The most famous domestic example of a cap-and-trade system, where businesses basically buy and trade pollution credits in a larger carbon market, is in California, which boasts a state economy larger than some nations. Washington, Bauman argues, couldn’t sustain that kind of system.

But perhaps more importantly, a carbon tax — and especially a revenue-neutral one that doesn’t actually raise taxes — has become the preferred policy for conservatives and businesses that want a price on carbon without creating new taxes or bigger government. In Washington state, which votes Democrat in nearly every national election but exhibits far greater political division on the local level, Bauman couldn’t couldn’t see a scenario in which they passed a price on carbon without the help of the business community and Republican lawmakers. A revenue-neutral approach seemed the best chance of bringing the unlikely supporters — manufacturers and conservatives — on board.

He just didn’t imagine that it would also lose him the support of some of the biggest names in the Washington environmental community.

The root of much of the Washington environmental community’s suspicion — and outright opposition — to Initiative 732 goes back to 2015, around the time that Bauman and CarbonWA were getting ready to take another swing at passing a revenue-neutral carbon tax in the state. The year before, Gov. Jay Inslee (D) convened a Carbon Emissions Reduction Task Force, charged with creating measures to offset carbon pollution throughout Washington. The final product was the Carbon Pollution Accountability Act, which Inslee introduced to the legislature for consideration during the 2015 session. Under the act, Washington would set a cap on emissions, requiring all businesses that produced emissions in excess of the cap to purchase credits on a carbon pollution market, similar to California.

At the same time, longstanding environmental groups, like the Washington Environmental Council and ClimateSolutions, began to rethink their own strategy. For years, they had labored to push environmental and climate action in the state, oftentimes rewarded with only incremental progress. So they decided to expand their view of the issues, looking to communities of color and labor organizations to broaden the state’s environmental movement into a larger social justice movement.

“Viewing climate change as an environmental body of work is way too limited,” Becky Kelley, president of the Washington Environmental Council, said. “It’s not really an environmental issue, it’s a broad, societal and economic issue.”

So environmentalists like Kelley set to work, bringing leaders from an array of causes — labor, social justice, religious, public health, business, and environmental — into a kind of social justice juggernaut known as the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy.

As soon as the Alliance came together in early 2015, they began working to help push Inslee’s cap-and-trade bill through the legislature. The idea of a cap-and-trade dovetailed better with the Alliance’s vision of sustainable climate action — they liked the idea of a cap on emissions, which would set a sure limit on carbon pollution. And that cap can be lowered over time, making sure that big polluters are forced to make serious changes that curb their carbon pollution. Those were policies, the Alliance felt, that would protect those most affected by the consequences of climate change and environmental pollution, which are most often communities of color and low-income communities.

But the Alliance knew that CarbonWA, led by Bauman, had another carbon pricing scheme in the works, actively collecting signatures and trying to decide whether to submit the initiative to the legislature at the end of the year, or attempt a voter bypass later in 2016. And while the Alliance supported the idea of a carbon price in theory, the new coalition was already stretched thin, throwing the brunt of its political weight behind Inslee’s cap-and-trade bill.

The two groups met early in 2015 to discuss strategy moving forward, eventually issuing a joint statement that they would not have two competing carbon pricing schemes on the ballot in November. The idea was that whatever version of a price on carbon ended up on the ballot, both sides would support it. But that didn’t happen. According to Kelley, CarbonWA decided to move forward with their carbon tax initiative on an accelerated timeline and present the signatures to the legislature at the end of 2015, rather than wait to gather signatures in the new year. According to Bauman, the Alliance simply failed to come up with a competing initiative in time to make the ballot. That meant that once cap-and-trade failed in the legislature, Initiative 732 was the only dog left in the climate fight.

“At that point, if you want to do something about climate change, there is only one thing that is on the ballot, so maybe you should support it,” Bauman said. But the Alliance didn’t support it — and some members, like the state’s largest labor council, voted to actively oppose it, leaving CarbonWA without a crucial block of support they had been counting on.

“I was really surprised by that,” Bauman said. “I continue to be surprised by that, and I continue to hope that they are going to change their minds.”

Becky Kelley, the Washington Environmental Council’s president, wants to be clear that this is a difficult situation. She has known and worked with some of the people who helped build the carbon tax campaign, and she speaks about them with kindness.

But she just doesn’t believe in the climate movement they are selling.

“Climate policy is not environmental policy. It is everything policy,” she said. “It is transformational, societal policy that touches economics and social justice and how we move and what we buy and where we live and all of the things.”

Opponents of the measure point to several specific shortcomings. First, the tax is revenue-neutral, instead of revenue-positive — meaning the revenue generated from the tax goes to cutting taxes elsewhere, instead of investing that money in new programs. From their perspective, a smarter policy would take revenue and invest in renewable energy and fuel-efficient transportation, which would ultimately hasten the transition to a green economy. The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, the Northeast’s answer to cap-and-trade, takes the revenue created by the carbon market and funnels it back into projects that increase energy efficiency or access to renewable energy. Such a model helps communities that would be most impacted by a price on fossil fuels to see their options for energy or transportation transformed in ways that work for them, not against them.

“Climate policy is not environmental policy. It is everything policy.”

“Otherwise, what we will see is that those that are least able to afford the taxes are bearing the brunt of not being able to afford more at the fuel tank, are unable to afford a clean car, and are forced to drive farther,” Rebecca Saldaña, executive director of Puget Sound Sage, a member of the Alliance that also opposes I-732, said.

I-732’s detractors also argue that CarbonWA’s boast of a revenue-neutral plan isn’t true — and that the plan would instead create a “budget hole” in a state that badly needs revenue.

They cite a Washington State Department of Revenue study that found the carbon tax, in its first six years of implementation, would cost the state about $797 million. In the grand scheme of Washington’s six-year, approximately $270 billion budget, that’s not a huge hole — but opponents say the state can’t afford even the smallest decrease in revenue. Since 2012, Washington state’s legislature has been held in contempt by the state supreme court for not adequately funding the state’s public schools, with the court levying a $100,000 daily fine beginning last August for each day the legislature has failed to fund the school system. In such an environment, opponents of I-732 insist the last thing the state needs is a revenue-negative tax — even one that would create a fairly negligible shortfall in the grand scheme of the overall budget.

But whether or not the tax is revenue-neutral or revenue-negative (and the environmental think-tank the Sightline Institute estimates it’s much closer to revenue-neutral than the state’s economists would have you believe) opponents’ main issue with I-732 has to do with the way that it was crafted, largely without input from low-income communities or communities of color.

“A handful of spokesmen cannot save our country,” Saldaña said. “We need to stand with communities that are most impacted and actually hear and listen to them, so that the things that [the authors of 732] have designed in their ivory tower and university is relevant to people that are actually living in pollution.”

They point to an interview Bauman gave to the New York Times’ Upshot, where he argued that the route to climate action was through the Republican party, and accused environmental activists of willingly using “race and class as political weapons” to achieve their policy goals. To opponents of 732 who already worried the policy didn’t take into account the needs of communities of color, Bauman’s remark was regarded as beyond tone deaf — a feeling not helped by the optics of the CarbonWA executive committee, which is both totally white and predominantly male.

“A handful of spokesmen cannot save our country. We need to stand with communities that are most impacted and actually hear and listen to them.”

“[Bauman] was very dismissive about the fact that we need to elevate the voices of those communities that are disproportionately affected by air quality issues and water quality issues,” Tammy Morales, a resident of South Seattle who has decided to vote no on the initiative, said. (Since June of this year, Morales has been employed with an Alliance-related organization, though she was not a member of the organization when I-732 was going through the initiative process). “Talking about how we were using race as a weapon and dismissing that those voices needed to be paid attention to, it was pretty off-putting.”

Communities of color, low-income communities — the people hit hardest by the impacts of pollution and climate change — have been largely excluded from helping to craft environmental policy, and policy in general, throughout history. Opponents argue that I-732 is just another example of that kind of policy process — an attempt to solve a problem without giving voice to the most affected and least listened to.

“If [I-732’s authors] had talked to those people in terms of what is needed, they would not have pursued this route and had a different policy on the table,” Saldaña said.

Instead, the authors of 732 elected to push forward with their policy without reconciling with the demands of social justice and environmental justice groups. The alternative was a ballot without any significant climate mitigation policy, and that simply wasn’t acceptable to them.

“I-732 ended up being the only real carbon pricing policy on the table,” Alex Lenferna, a campaign fellow and Fulbright Scholar, currently getting his PhD in Philosophy at the University of Washington, said. “I-732 is a really, really great policy that does a lot of great work, and it’s the only carbon pricing policy that we have on the table now, and that we will likely see for the foreseeable future in Washington.”

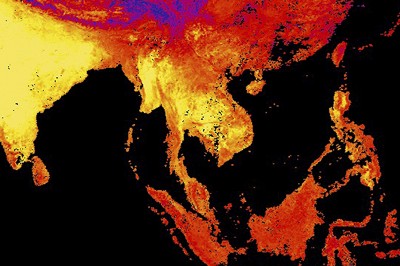

The news about climate change is rarely good, but lately, it seems to come as an almost-constant stream of dire warnings. The world just experienced its 16th in a record-streak of warm months. August tied July as the hottest month ever recorded by NASA in its 136 years of record keeping. Louisiana was devastated by a 1-in-550 year flood event. Droughts and weak monsoons have so depleted South India’s water resources that violence recently erupted over an order to share water. A report released by Oil Change International this month found that if all existing fossil fuel projects operate through their expected lifetimes, the resulting emissions will push the world well above 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming. And yet, the Republican nominee for president advocates opening up more land and oceans to drilling while energy companies fight for more pipelines through the heart of the country.

“We think [opponents of I-732] are either not reading or misreading the science, which is telling us that we have five, maybe 10 years to really start bending the emissions needle, and so years become really precious in that timeframe,” Kyle Murphy, CarbonWA’s campaign co-director, said. “We think that urgency is really real.”

The Alliance’s preferred policy — a cap on emissions and a fee on carbon that is reinvested into green infrastructure and energy projects — has historically been difficult to sell to conservative politicians and businesses. It creates more bureaucracy and requires more government intervention than a carbon tax. The goal is to place more of the financial burden on polluters than taxpayers, something that would likely catch the ire of powerful business groups like the Western States Petroleum Association, a fossil fuel focused trade group that has been surprisingly quiet on Initiative 732.

“These harmful and negative impacts are happening now, and they are really urgent to deal with.”

Combine the potential for a strong, well-funded opposition campaign with the electoral dynamics of the next few election cycles — 2018 being a non-presidential election unlikely to draw high voter turnout — and it could be years before a policy like the one embraced by the Alliance could see an election with the kind of engaged voter turnout expected this year.

But setting aside warnings from the scientific community and an analysis of electoral dynamics, the people behind Initiative 732 emphasize that while communities of color might not have had a representative voice throughout its creation, the end result is a policy that does a lot to help low-income and communities of color — by taxing externalities, making the tax code more progressive, and funding the Earned Income Tax Credit.

“This does a lot of good for racial justice,” Lenferna said. “If you read the latest Black Lives Matter platform that came out…94 percent of our policy is in the Black Lives Matter platform, because regressive tax codes, pollution, and climate change all fall disproportionately on minorities and communities of color.”

“That’s not to say that our policy is perfect — we definitely could have done things better,” he added. “But the thing is that these harmful and negative impacts are happening now, and they are really urgent to deal with.”

The idea that either side could have done something better is palpable when speaking both to members of CarbonWA and members of the Alliance. No one seems to be 100 percent happy with the situation in Washington; it has turned traditional allies into uncomfortable enemies, and caused groups to fracture, at least internally, over the best path forward. But for better or worse, CarbonWA’s initiative is the only carbon price on the ballot — and the people who support it are doing everything they can to make it law of the land come November 9.

“This is what is in front of us on our ballot. This is the opportunity that is in front of us right now.”

That means doggedly working to convince as many people as possible to help them in their quest. And they’ve had some success, especially with groups that boast a strong, grassroots kind of membership. In July, the Washington state chapter of the Audubon society made waves when it publicly endorsed Initiative 732, something few visible environmental groups had done. It was a decision the group labored over for more than a year, convening meeting after meeting at both the state and local level to gauge members’ feelings about the carbon tax.

In the end, however, the choice was fairly simple: Audubon supporters are bird people, and climate change is the number one threat to birds.

“This is what is in front of us on our ballot. This is the opportunity that is in front of us right now,” Gail Gatton, executive director for Audubon Washington, said. While the group admits the measure isn’t perfect, Gatton believes climate change is happening too rapidly to let an opportunity like Initiative 732 pass by.

“I think people get that climate change is happening and anything that we enact now will probably take a bit of time to get in motion anyway, so there’s that sense that you don’t want to wait for anything different,” Gatton said.

With only a few weeks to go, the race to pass the carbon tax remains tight: The most recent poll shows the initiative trailing, but just slightly, with 34 percent in favor and 37 percent opposed. Almost a third of state voters are undecided. And while conventional wisdom might suggest that undecided voters tend to break for the opposition, Bauman remains confident in CarbonWA’s strategy.

“We need to reach out to voters who care about climate change,” he said. “If we can convince voters who care about climate change to vote yes on 732, we win.”

But getting those people to vote yes on I-732 means more than just convincing them that this policy will help fight climate change; it also requires convincing them that this policy is the right way to tackle climate change. And that’s where the debate becomes more complicated, because at the end of the day, neither side is wrong. It is both true that climate change is a crisis that requires swift action to curb carbon emissions, and that low-income and communities of color have historically been absent from crafting environmental policy. But these communities are also hardest hit by the consequences of climate change — and while they would certainly suffer from inadequate policy, they’d also suffer from a lack of climate policy altogether.

“If you care about climate change, then this is what is on the table. And it is pretty darn good.”

That leaves voters in the state with no easy answer, and activists involved with the initiative with a tough road ahead.

Bauman, for his part, is not willing to accept that opposing I-732 — even if it breeds different action in the long-term — is better than passing something this year.

“What is wrong with taking a swing at the ball with a policy that is one of the strongest carbon prices in the world and the biggest improvement to the tax code in 40 years? What more do you want?” Bauman asked. “Yeah, clearly there is other stuff that people want, but if you care about climate change, then this is what is on the table. And it is pretty darn good.”

Now it’s up to Washington voters to decide whether pretty darn good is good enough.