It was a muggy night in June 2004 when someone approached Tyrone King on the street corner in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The guy was looking to buy a few “slabs” of cocaine. King struggled with drug addiction, and said the guy offered to “get him high” if he helped him out. The two walked less than a block, where someone looking to sell lived on the fourth floor of a red brick apartment building.

The buyer turned out to be an undercover cop with the Bridgeport narcotics team. Police claim King took $20 inside the apartment and returned with two small bags containing .14 grams of crack. King plead not guilty to the charges, but a jury convicted him of two felonies: one for selling narcotics, and one for doing it within 1500 feet of a school.

Several hundred yards away from the dealer’s apartment was Kolbe Cathedral High School. It didn’t matter that the deal took place at 10 pm, indoors, and well after Kolbe’s students had left for summer vacation. The undercover officer took the stand during King’s trial and simply pointed to a map. An investigator for the state’s attorney’s office told the jury he measured 911 feet between the apartment and the high school. That was all the prosecutors needed to prove.

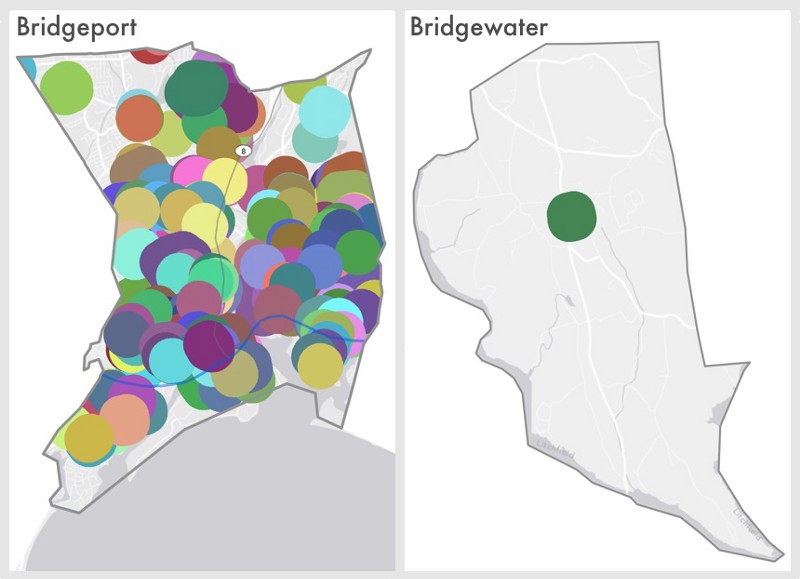

Police could have pointed to any spot on that map of Bridgeport: almost the entire city falls within a drug-free zone. But had King committed the same crime in Canaan, Bridgewater, or any of Connecticut’s other suburbs or towns where drug-free zones cover relatively little ground, he likely would have faced one fewer felonies, and three fewer years in prison.

“There’s an additional penalty just for residing in an urban zone,” said Aleks Kajstura, legal director for Prison Policy Initiative. “The law has the power to push people toward pleading guilty to avoid mandatory minimum charges.”

In total, King was sentenced to 13 years in prison. His sentence was later reduced, when courts found his lawyer had failed to advise him of his option to settle out of court. He is now in custody on a different charge and could not be reached for comment. His lawyers declined to comment on the case.

Drug-free zones seem like a common sense solution to what many consider a big problem: to keep drug dealers from selling to children, increase the penalties for drug crimes near schools. States started passing versions of the law in the 1980’s, riding the wave of panic over crack cocaine and the mounting enthusiasm for the War on Drugs.

“Schools have long been the target for drug pushers looking to find new dependent sources to sell their drugs supply,” said former Shelton, Connecticut Mayor Michael Pacowta in a 1989 hearing on the state’s bill. “[This] sends a strong message to the state’s drug dealers to stay away from the children.”

But the zones have ballooned to include entire cities. They now hit almost any urban drug crime with an extra felony, one that was meant to punish dealing to school kids. Meanwhile, drug offenders in whiter, wealthier, spread-out suburbs and towns rarely face the same consequences.

“It comes up in just about every drug case, really,” said New Haven public defender Bevin Salmon. “The intent of the legislation is to target dealers who would sell specifically to children or within a very close proximity to a school, [but] it nets just about everyone. It gives the prosecutor a lot of discretion, a lot of leverage.”

Studies show very few of the drug-free zone charges have actually involved children. In 2005, The Connecticut Legislative Assembly reviewed a random sample of 300 cases and found that apart from three cases in which students themselves were caught with drugs, none of the arrests had any connection to schools or their students. Nearly 90 percent occurred outside school hours, and the majority took place within the home.

Apart from three cases in which students themselves were caught with drugs, none of the arrests had any connection to schools or their students.

While momentum builds to rethink the severe sentencing laws that are overcrowding state and federal prisons, relatively few lawmakers have addressed the “sentence enhancement zones” blanketing urban communities. At least 29 states have taken steps to reduce mandatory minimums since 2000. Yet only seven states have addressed drug-free zone laws specifically. At least three states (Arkansas, Hawaii and Louisiana) have expanded the area subject to a stiffer sentence.

“I don’t think they’re getting any attention in the broader conversation on the federal level,” said Nicole Porter, director of advocacy for the Sentencing Project. Porter notes that none of the sentencing reform bills being considered by Congress address the federal law establishing a 1,000-foot drug-free zone.

The laws can add years to already severe drug sentences due to mere circumstance. In Alabama, those convicted of selling drugs within three miles of a school or university have five years added to their sentence, and another five if they’re also within three miles of public housing. Utah lawmakers have created a 1000-foot buffer zone around not just schools, but also parks, movie theaters, shopping malls and parking lots.

Indiana’s Supreme Court recently reduced one man’s 20-year sentence for possession of 1.15 grams of cocaine. Cops had pulled him over 125 yards from a private school housed inside a Methodist church, on grounds of a “window tint” violation. Had they stopped him 625 feet earlier, he would have faced a maximum of three years in prison.

“Nothing in the record suggests that the driver of the car had anything to do with the location of the stop,” the judge found. “The nature of his offense in this case renders his twenty year maximum sentence inappropriate.” Indiana has since shrunk its zones from 1000 to 500 feet and only applies the law “when a child is likely to be present.”

From Porter’s perspective, drug-free zones remain because “at the end of the day, these questions boil down to politics. The school zones have their most impact in urban areas where the electorate is often poor and is often of color.”

92 percent of Bridgeport residents live in a drug-free zone, while only 8 percent of Bridgewater residents do.

CREDIT: Research and graphics by Prison Policy Initiative

Bridgeport is home to roughly 37,000 kids, a third of whom live below the poverty level. You can’t walk more than two blocks in the city without running into one of 37 public schools, four charter schools or five public housing buildings. Countless daycare centers are also housed inside commercial buildings or wedged into strip malls along busy highways. As a result, drug-free zones cover almost all of the city’s 16 square miles. Researchers at the Prison Policy Initiative found that 92 percent of the city’s residents live within an enhanced sentencing zone.

“Everywhere’s a school zone, so it doesn’t make a difference,” said Pernell Clemonts, who was charged with conspiracy to sell narcotics within 1500 feet of a school when he was 16 years old. Cops caught him with drugs in front of his apartment, which was half a mile from an elementary school.

It’s not just Bridgeport — in New Haven, the only part of the city not subject to higher sentences is the Yale golf course. In Hartford, it’s the airport, industrial yard and governor’s mansion. But in smaller, more rural towns like Bridgewater, only 8 percent of residents live in areas with an added felony charge for drug offenses.

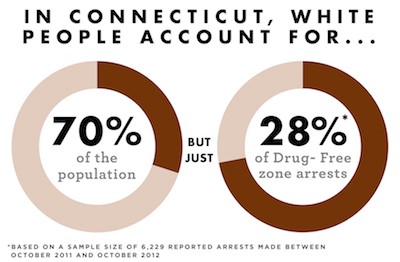

Unsurprisingly, that “urban penalty” falls disproportionately on communities of color. Data analyzed by ThinkProgress suggests that though whites make up over 70 percent of Connecticut’s population, they account for as little as 27 percent of arrests under drug-free zone laws. Of 6,229 reported arrests made under Connecticut’s drug-free zone laws between October 2011 and October 2012, only 1,730 were of white offenders.

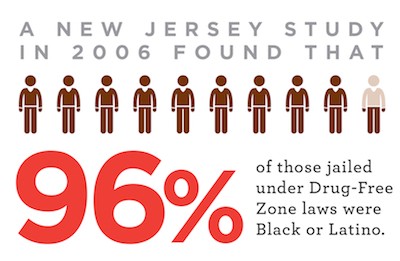

Studies elsewhere show the same racial impact. A 2007 study by the New Jersey Commission to Review Criminal Sentencing found that “nearly every offender (96%) convicted and incarcerated for a drug-free zone offense in New Jersey is either Black or Hispanic.” The state has since passed a law eliminating mandatory minimum sentences for drug zone offenses.

Supporters of the drug-free zones say they still send an important message. “The farther away you can get them from the school the better, so kids don’t have to see drugs or be put in danger,” said detective Harold Dimbo with the Bridgeport Police Department. “If anything, make it 1800 feet.” Dimbo recognizes that the zones cover almost all of the city, but says that’s an inevitable consequence in compact, urban areas.

“If you don’t sell drugs, you don’t have to worry about 1500 feet. You don’t have to worry about 10 miles,” said Sergeant John Webster, head of the narcotics unit at the New Britain Police Department. “The more we allow, the bolder people get.”

But others say the bigger the zone, the weaker its power to drive drug dealers away. “The theory is you want to have an enhanced penalty for someone who is selling drugs on or near these places where young kids would be,” said Justice David Borden, chair of the state’s Sentencing Commission. “[But] if every place is a specially protected area, no place is a specially protected area.”

“If every place is a specially protected area, no place is a specially protected area.”

In areas where drug zones don’t cover the whole city, the laws create odd disparities. Dealing drugs from apartments on opposite ends of the same complex could result in different sentences. As a University of Connecticut student pointed out in a recent op-ed, getting caught with drugs in some dorms could carry bigger consequences than in others.

A 2004 study of Massachusetts’ drug-free zones by a former state prosecutor specializing in narcotics found that despite the laws, more drug crime actually occurred within the zones than outside them. Less than 1 percent of those cases involved selling drugs to minors. In 2012, Massachusetts legislators passed a bill that reduced the size of the zones from 1,000 to 300 feet, and only applied the law between 5 am and midnight.

Lawmakers in Connecticut will soon vote on a similar proposal to reduce the zone from 1,500 feet — one of the largest in the country — to 200 feet. “We talk about a drug-free school zone in New Haven, that’s called New Haven,” said Democratic State Senator Gary Holder-Winfield, one of the bill’s sponsors. Holder-Winfield represents the 10th district, which covers New Haven and West Haven. “In order for school drug zones to work there has to be a differentiation between the penalty for some areas and others.”

State Sen. Holder-Winfield says that because dealing to minors already carries its own, separate consequences, there’s no need for a drug-free zone. “The sale to a minor equals an enhanced penalty, and then it doesn’t matter whether you’re within 1500 feet or 4000 feet,” he said.

State Sen. Holder-Winfield says he’s introduced the bill every year since he took office as a state representative in 2008. But the proposal has faced strong opposition.

Republican State Representative Prasad Srinivasan, who represents the suburban community of Glastonbury, said he was “appalled” Connecticut was even considering the bill. “We are all well aware that no one system is going to be fitting every town every municipality,” he said in a March testimony before the state’s judiciary committee. “But regardless of that, the message we need to send loud and clear is that we will not have drugs within that area.”

State Rep. Srinivasan’s office declined a request for comment.

Many citizens who submitted written testimonies on the bill voiced similar concerns. “Why on earth would we want drug dealers and users closer to schools?” wrote one parent. “Last I heard, dealing drugs to school kids was illegal.”

“Why on earth would we want drug dealers and users closer to schools?”

But to LaResse Harvey, a community organizer from New Britain, such rhetoric distracts from the real discussion. “I am tired of the old, ‘what about protecting our children?’ Lately a lot of our children are the ones selling,” she said. Harvey works for Connecticut criminal justice advocacy organization A Better Way Foundation, which has been pushing to reform the drug-free zones since the early 1990’s. “It’s our children that we’re preparing for prison and not college or careers.”

Adding a buffer zone to public housing is “in itself discriminatory,” Harvey said. “Why is that even in there? Who lives in public housing? Majority black and Latino, majority poor people. People in private homes aren’t subject to the same laws.”

Very few people arrested on drug-free zone charges are actually convicted of the crime. In Hartford, only 11 percent actually serve the mandatory minimum of three more years in prison. In the city of Wallingford, it’s less than half of 1 percent.

But lawyers say those statistics can be misleading. “The fact that you’re not seeing successful prosecutions with these enhanced penalties doesn’t mean they’re not having an impact on our justice system,” said David McGuire, staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Connecticut, who testified in support of the bill. “A prosecutor will use the possibility of prosecution as leverage to get someone, usually someone of color, to plead to a harsh deal.”

A recent report by Human Rights Watch detailed how federal prosecutors have used the threat of mandatory minimum sentences to get drug defendants to waive their right to trial. In total, 97 percent of those facing federal drug charges plead guilty and settle out of court.

Some prosecutors say they don’t bring the charges that often. “We rarely use it. The factors we use are does the person have prior sale convictions? Do they have a prior gun conviction?” said supervisory assistant state’s attorney David Strollo from New Haven. “Obviously if someone is going to be selling right on the playground or in the school you’re going to look at that differently than someone down the block.”

As Hartford public defender Bruce Lorenzen sees it, “It’s just sort of stupid. It doesn’t modify anybody’s behavior, they don’t care where they are. It’s viewed by even the prosecutors as such a draconian measure that they don’t even think it’s reasonable.”

But many say leaving it up to prosecutors’ discretion gives them too much power. “It gives prosecution a very broad and excessive weapon in the prosecutorial holster so to speak, because it can be used arbitrarily,” Justice Borden said.

Several charged under the laws said it affected their decision to accept a plea bargain. “They’re just filler for your rap sheet. They’re always thrown out,” said Thomas (last name withheld), who was arrested on drug charges within 1500 feet of Marina Village, a public housing complex in Bridgeport. Thomas lived around the corner from the building. “The more felonies they can add up, the more likely you’ll be to plead guilty. I’m sure I would have gotten at least five or ten years if I had gone to trial.”

Clemonts, who was a first-time offender, had a similar experience. The charge for selling within 1500 feet of Smalley Academy was dropped when he plead guilty to possessing narcotics. He received seven years of probation. “They use it as a way to get you to plead guilty to something else,” Clemonts said. “I had no choice. I couldn’t afford to go to trial.”

To Clemonts, who grew up in New Britain, the different application of the laws is clear. “You read the suburban newspapers, you don’t see people with so many of those school zone charges,” he said. “You come over here, New Britain, Hartford, you see school zone charges all the time. Because more people are poor.”